The debate on Turkish foreign policy's "axis," "strategic autonomy" and "normalization" policy was recently revived by Parliament's approval of Sweden's NATO membership, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's Cairo trip and Türkiye joining the European Sky Shield Initiative.

I deliberately use the verb "revive" here since foreign policy has played a crucial role in Türkiye's transformation throughout the Justice and Development Party's (AK Party) 21-year tenure. Hence, foreign policy emerged as a focus of attention – whether observers described it as "harmonious with the West" or an "axis shift."

Türkiye's post-2013 foreign policy, in particular, was criticized by the opposition as "isolation" and an "axis shift" as the country experienced tensions with the United States and the European Union as well as some Arab states while strengthening its cooperation with Russia after 2016 – which included the purchase of the S-400 air defense system.

Likewise, the AK Party government's 2020 policy of "increasing the number of friends" was promptly described as a U-turn motivated by desperation.

In truth, Türkiye's foreign policy in 2013-2020 and since 2020 had the same objectives: To defend Turkish interests, adapt to changing regional-global circumstances and consolidate Turkish strategic autonomy.

All those goals, in turn, were linked to Türkiye's determination to redefine its position and role within the international system to adapt to emerging risks and

chaos in an increasingly multipolar world.

In other words, the "more friends" approach was about cementing the gains and eliminating the costs of the "pulling oneself up by one's bootstraps" period.

Accordingly, Türkiye did not pursue an "abnormal" policy as it experienced tensions with the U.S. and the EU over Turkish military operations in Syria and with Greece over the Eastern Mediterranean – just as Türkiye, a supporter of NATO's enlargement, agreeing to Sweden's admission did not amount to the "end of a chapter."

Reciprocal normalization: Multilateral effort

"

Normalization" is a reciprocal effort by multiple players to repair and improve their relations. It is not a unilateral decision by Türkiye to revise its approach.

Türkiye has indeed been taking steps to repair its relations with the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, Greece and Egypt, and transform those relations into strategic partnerships. It also promotes a positive agenda with the U.S. and the EU.

Could one argue that those initiatives are unilateral? The answer is no. Indeed, normalization is taking place because it is reciprocal and all the relevant players have been taking stock of their policies and positions. For example, normalization may not have taken place had the

Donald Trump administration's "orb" project not failed. We could have witnessed quite different developments if the Gulf states had successfully contained Türkiye.

Again, de-escalation in the Eastern Mediterranean possibly would not have been possible without Türkiye's military aid to the Sarraj government in Libya to end the civil war and the maritime delimitation agreements between the Turkish and Libyan governments.

Let us recall that normalization with Israel was stopped in its tracks by the ongoing massacres in Gaza.

Ankara's shifting alliances

The situation with NATO and the EU is much more obvious. Ankara has always cared for its alliances with the West, yet wanted to change the nature of those alliances.

It criticized the objections against NATO's fight against terrorism and attempted to make changes on that front. In other words, the Turkish government experienced tensions with the West over the PKK's Syrian offshoot YPG and the Gülenist Terror Group (FETÖ) due to its vested interests. Türkiye also took jabs at the West for failing to meet its defensive needs and explored new options.

The state of affairs with the EU is no different. The European governments effectively suspended Türkiye's admission process in 2007, even though Ankara still views EU membership as "strategic."

Again, Ankara repeatedly said that Europe could not defend itself without the Turks – which is why Türkiye joining the Sky Shield Initiative is perfectly "normal."

It goes without saying that none of those developments mean that Türkiye will end its cooperation with Russia in line with old-fashioned bloc politics. Nor do they mean that the Turkish balancing act will end.

Indeed, it is no coincidence that Russian President Vladimir Putin sees the Turks as the "most reliable" of partners and recently said that the war in Ukraine could have ended during the talks in Istanbul.

Emerging powers: India, Brazil, Türkiye taking center

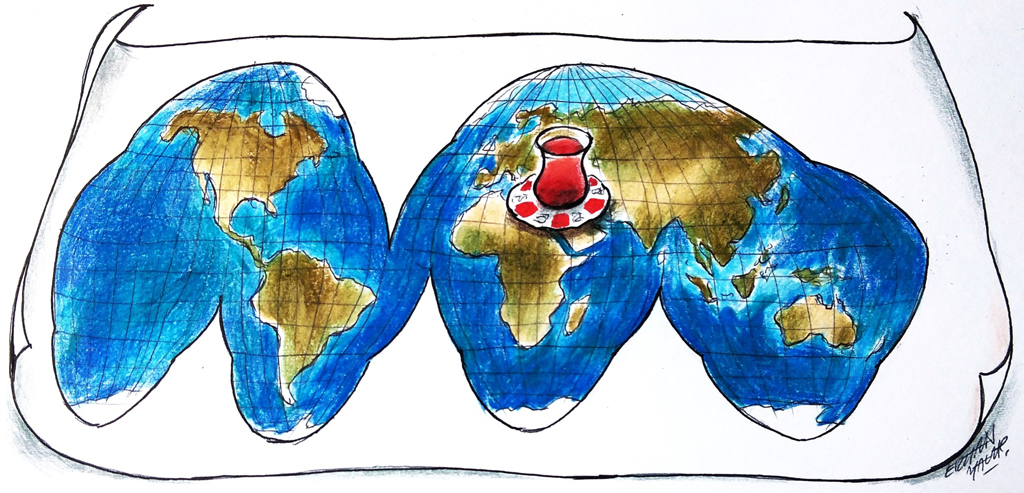

The world is heading toward a period of multipolarity with major risks. The COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian-Ukrainian war, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict expedited the emergence of that chaotic situation, which requires emerging powers like India, Brazil and Türkiye to assume an important responsibility.

First and foremost, we must get ready to face the vacuums, chaos and risks that great power competition will generate. We need stability and cooperation in many fields, including trade, energy, technology and security. Again, it is important to recall that the Western-centric order giving way to multipolarity does not necessarily entail the end of hierarchy.

We witnessed how the supposedly rules-based unipolar world order led to sovereignty and human rights violations. It is possible that the emerging state of multipolarity will be more chaotic and more dangerous. That is why Türkiye – insisting that "the world is bigger than five" – does not merely speak up against the unjust aspects of the Western-centric world order.

It also highlights the problems with great power competition between the U.S., China, Russia and the EU to reject new forms of polarization. At the same time, the country seeks to be part of the solution in places like Ukraine and Gaza. There is reason to believe that Türkiye will further strengthen its position and role within the international system over the next years.

[Daily Sabah, February 23, 2024]