In the 1990s, one of the most frequently used analogies for Turkish foreign policy was about "missing the train." The security dilemma that Turkey found itself in after the end of the Cold War generated a crisis among some observers of Turkish foreign policy. The feeling of abandonment from the Western world in the aftermath of the Cold War as a result of losing frontline status deeply influenced the perspective of foreign policy. The refusal of Turkey's membership application to the EU during these years also contributed to this approach, and "missing the train of the EU" became the dominant fear in Turkish foreign policy. Later, the 1997 Luxembourg Summit and the exclusion of Turkey from the EU enlargement process traumatized the fears. Although the volume of trade with EU member countries was increasing rapidly, the feeling of total loss and abandonment prevailed, and a feeling emerged that Turkey cannot survive without being part of the EU.

The Helsinki Summit and EU reform packages in its aftermath broke down this fear, but the 2003 war in Iraq and the March 1 crisis between Turkey and the U.S. transformed this fear as an anxiety of abandonment in Turkey by the U.S. Although some observers in Western capitals called this disagreement as "Turkey turning away from the West," in Turkey some other observers dramatized the same developments as the "West's turning away from Turkey." The same observers continued this line of thought throughout the first decade of the millennium. They preferred to internalize the critiques of some observers in Western capitals and interpreted the up and downs in bilateral relations between the U.S. and Turkey through the discourse of the "shift of axis," "Who lost Turkey?" and "sick man of Europe, again." Although positive signs in relations during the Obama administration calmed this anxiety down a little, similar analyses reappeared in each and every instance of disagreement between the two countries.

With the disagreement between Turkey and the U.S. and some European allies about the coup in Egypt and the conflict in Syria, similar criticisms started to take place regardless of the nature of Turkey's position. The analysis of Turkey being alone in the wilderness of the Middle East without any allies or friends has generated a new "fear factor" for the same observers.

This perception revived in recent months in regards to the disagreement between Turkey and the U.S. over the question of Kobani and the problem of ISIS. While there were arguments about Turkey's isolation from the international community, we experienced one of the busiest visit schedules to Ankara by foreign dignitaries. One after another, U.S. Vice President Joe Biden, Russian President Vladimir Putin and British Prime Minister David Cameron visited Turkey. Turkey assumed the G20 chairmanship in the meantime, and the Turkish president joined the Turkish-African Economic Cooperation Summit in the same period. The Turkish prime minister at the same time paid two very important visits to Iraq and Greece to reset Turkish relations with its neighbors. There was a major conference in Istanbul in the meantime on the New Silk Road initiative.

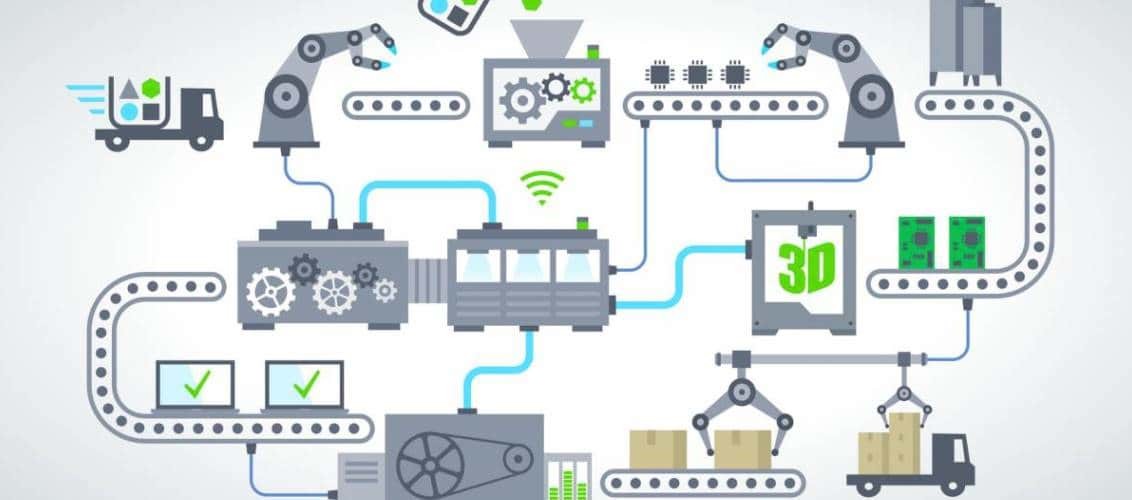

This approach of trying to analyze Turkish foreign policy under constant threat of abandonment is leading to a problematic understanding that Turkey will lose everything in the case of a disagreement with major powers. Although Turkey's relations with the EU and the U.S. are critical, as a result of its security partnership, alliances and commitments but also in terms of economic relations, there are two trends that are deeply influencing foreign policy in general and Turkish foreign policy in particular. On the one hand, the foreign relations of Turkey are being diversified to include multidimensional relations with multiple different actors both in its region and in the globe. And secondly, the international system is being diversified to include different major actors and have multiple centers of gravity. As a result, relations among states are becoming more