The excitement Turkey generates in the Arab world and beyond (the Balkans, Europe and parts of Africa can easily be added to the list) seems to be sustained by the confluence of substantial changes in three areas: Turkey, the region and the world.

Turkey's increasing presence and influence in the Middle East cannot be explained by one single factor or the willingness of the Justice and Development Party (AK Party) government. Prime Minister Erdoğan's one-day visit to Baghdad, the first by a Turkish head of state, is indicative of Turkey's great potential in Iraq and beyond. The current international order functions without a center or with multiple centers, which amounts to the same thing. The centers of the world are up for grabs, and there are no self-proclaimed winners on the horizon. Major shifts in the regional power balance propel new actors into the arena. A post-American world order is likely to produce new regional giants.

The Arab world is hostage to the memories of a glorious past, a miserable present and a precarious future, unknown yet filled with promises. It is searching for a presiding idea and a leadership that it can trust. A post-American and post-nationalist Arab world will project a new cultural and political imagination. Such a new beginning may take the Arab world beyond the dungeon of victimization, on the one hand, and self-destructive policies, on the other.

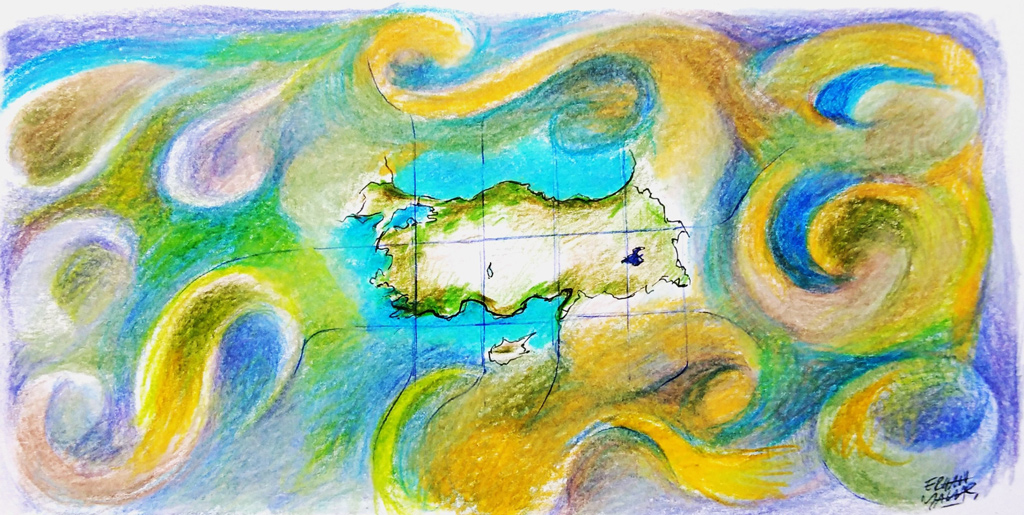

As for Turkey, it is a modern country that is, by all accounts, larger than a nation-state and smaller than an empire. Turkey is just beginning to act like the heir of an empire whose power of imagination, for better or worse, still hovers over those of Turks, Arabs, Persians, Kurds, Bosnians, Macedonians and others in our vast neighborhood.

It would be too simplistic to explain Turkey's rising profile in the Arab world with the Islamic credentials of the AK Party leadership. No doubt, personalities play a significant role in international relations. The personal investment and engagement of a political leader makes a difference in times of normalcy and crisis. But it is equally true that strong personalities do not come out of the blue for no reason. They emerge at the intersection of a number of factors and go beyond personal geniuses and individual heroism. What the Arab world sees in Turkey today, be it reality or fantasy, is more than the warmth of personal relations.

One way of understanding Turkey's new image in the Arab world is to look at what drives the minds and hearts of the so-called Arab street. For this, we do no better than tuning into Anthony Shadid's masterful narrative of the lives of Iraqis in his "Night Draws Near: Iraq's People in the Shadow of America's War." Struck by the rare appearance of the word hurriyah (freedom) in the daily conversations of Arabs, Shadid, one of the finest and most conscientious journalists around, notes that the word adl (justice) commands a heavy presence in all political talk in the Arab world. It is a "concept that frames attitudes from Israel to Iraq. For those who feel they are always on the losing end, the idea of justice may assume supreme importance" (p. 18).

In a world bleeding from the wounds of human greed, ignorance and injustice, every act of justice is immediately owned by countless people around the world. Turkey has been able to capture the imagination of Arabs and other Muslim nations for the sole reason that its acts have been received as serving justice not just for the Turks and the Turkish national interest, but for everyone yearning for justice in the region and the world.

What is new and exciting is the willingness of the new Turkish policy makers and civil society actors to engage in the corridors of regional diplomacy, while at the same time maintaining good relations with the US, Europe and Russia. This is more than a matter of will. It heralds a new imagination, a different geo-strategic map and a new set of principles by which Turkey wants to engage its immediate neighbors and global actors. And once this is ac