The Syrian refugee community and the question of irregular migration have been attracting renewed attention in recent weeks. Essentially, the government and the opposition agree on the right course of action regarding irregular migrants from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, Iraq and some African countries: Defending the nation’s borders and preventing illegal migration. Indeed, government officials have announced that authorities have been deporting illegal immigrants and had the necessary precautions not been taken, Turkey would be hosting up to 10 million illegal immigrants today. It is impossible for Turkey to put a permanent stop to the problem given its geographical location and its recent transformation from a transit country to a destination. Quite the contrary, the country is compelled to deal with irregular migration in the short, medium and long terms.

The question of Syrian refugees, whose population has reached nearly 3.77 million according to official data, is somewhat different. The issue will certainly be one of the top topics in the 2023 elections – as it was in 2018.

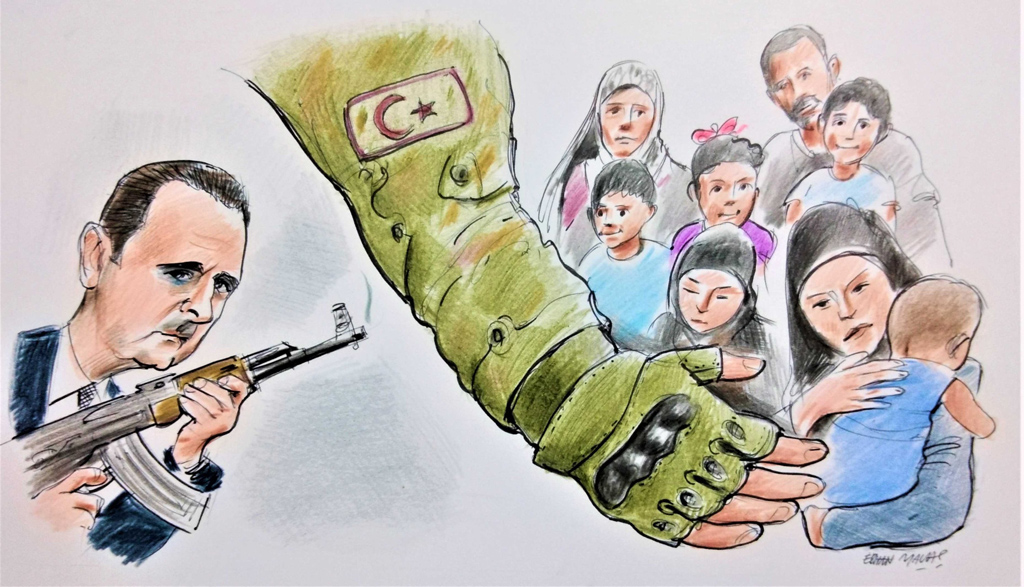

The future of Syrians, who fled the Bashar Assad regime’s oppression and remain under temporary protection in Turkey, gives rise to a multidimensional public debate regarding who bears responsibility for the “open door policy” that Turkey initially implemented, Turkey’s role in the Syrian civil war, the method/timing of the refugees’ return, the impact of anti-refugee sentiment on party politics and the question of xenophobia.

Critics from opposition

The opposition frequently criticizes the Justice and Development Party (AK Party) government’s initial policy response to the Syrian civil war, specifically targeting the “open door policy” toward asylum-seekers. Leaving aside the humanitarian aspect of that policy, they accuse the AK Party of something much more serious. Most recently, the Felicity Party’s (SP) Chairperson Temel Karamollaoğlu took a page out of the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) playbook and alleged that Turkey had destabilized Syria. That claim obviously disregards the fact that Turkey attempted to work with Assad in March-August 2011. It also omits the violence that started after the Assad regime arrested a number of middle school students who wrote anti-government slogans on a wall, killing one of them in the process. Urging Assad to implement reforms to promote stability and security in Syria, Turkey did not support the opposition (e.g., the Free Syrian Army (FSA)) for a long time. Indeed, the Turkish government has been so respectful of Syria’s territorial integrity that it did not launch any cross-border operations until 2016, when terrorist groups like Daesh and the PKK/YPG gained control over large chunks of territory. As such, the opposition’s argument – that Turkey would not have received so many asylum-seekers had the government not clashed with the Assad regime – is detached from reality and out of sync with the humanitarian situation. In retrospect, one could argue that it would have been better for Turkey to establish safe zones – in a broader sense – at the time. It is another fact, however, that the Gülenist Terror Group (FETÖ) prevented that step.

AK Party’s ‘Syria policy’

It is not surprising that the CHP, the Good Party (IP) and the SP criticize the AK Party’s Syria policy – including its treatment of asylum-seekers – as they criticize all the other policies that the government adopted over the last two decades. This case, however, presents them with a serious problem, as the chairs of the Future Party (GP) and the Democracy and Progress Party (DEVA), who sit around

the opposition’s roundtable today, played important roles in Turkey’s Syria policy at the time. Whether the opposition leaders accuse Turkey of meddling in Syria’s internal affairs or question why the country admitted so many asylum-seekers, GP Chairperson and former Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu and DEVA Chairperson and former Economy Minister Ali Babacan, who are with the opposition now, have to answer those questions no less than the current administration. It goes without saying that the opposition’s “table for six” will find it difficult to devise a common agenda. Obviously, one cannot help but wonder how they intend to criticize the AK Party government without discrediting their current partners. For the record, that contradiction is not limited to the Syria policy. It relates to many areas, including various foreign policy issues and privatization.

The fact that the CHP leadership, which used to pledge to send back the Syrians “right away,” is now saying that the process will take two years is a sign that they are becoming more reasonable. One way or another, the government and the opposition need to agree on a similar policy regarding this enduring issue. The government has been talking about the refugee community’s “return” since 2018. The policy of setting up safe zones in Syria, which dates back to 2016, serves the counterterrorism agenda as well as the repatriation of Syrians. Turkey currently maintains a military presence in the Syrian province of Idlib and the safe zones, keeping some 5 million Syrians within their country’s border. Meanwhile, some 500,000 asylum-seekers have voluntarily returned from Turkey.

The question of asylum-seekers can only be addressed by integrating the “harmony” and “repatriation” policies. Let us not lose touch with common sense in the relevant discussions. Sadly enough, some even claimed that the AK Party was using the Syrians for “Islamist social engineering.”