Had Turkey not gotten involved in the Syrian crisis and had it followed a different foreign policy, what would Turkey gain? This question is worth exploring even only as a thought experiment. We assume this question was asked in the very beginning of the Syrian crisis. We can also safely assume that those who heavily criticize Turkey’s foreign policy would answer this question positively. Yet, it is not clear how they would arrive at this answer.

First of all, which Turkey are we talking about? The AK Party that came to power during the invasion of Iraq had to get involved with the “East” while maintaining the distance and carrying the burden that came with Turkey’s early republican Westernization legacy.Turkey drew its foreign policy in this uncharted field by being thrown into fire with the invasion of Iraq and the Arab Spring. Turkey owned the calls for democratization at once with what could also be interpreted as geopolitically risky moves.

It is obviously clear that those moves were Turkey’s, who stood against the Syrian crisis, prelude to its stance in the region for the next decade. This was the Turkey that stood, not with the Baath regime, but with the people who mobilized against the regime. Coming back to our original question: What could happen had Turkey not stood with the people and against the Baath regime?

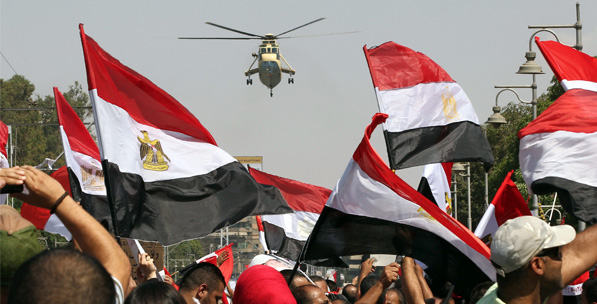

Such a foreign policy would force Turkey to face problems with Tunisia, Libya and most importantly Egypt. Turkey, while trying to avoid the Syrian crisis, would have difficulty explaining itself to the peoples and the governments of Tunisia, Libya and Egypt that have shaken the region to its core. Turkey would have to pay a heavy price in order to compensate for what has been defined as an “axis shift” in Western foreign policy discourse. In fact, such a fall out would not be limited to an axis shift but would leave the entire Turkish foreign policy in shambles.

Had Turkey supported the Baath regime and had it interpreted its immoral insistence to ignore the massacres as a geopolitical move, it would not only make it impossible to explain itself to the peoples of the region but also to its own people. Had Turkey favored the al-Assad regime instead of the Syrian people, it would not only lose its legitimacy and its claim to being the democratic model for the region, but also would find itself in a deep hole out of which it would not be able to climb for years to come. The cost to pay for such support would not only leave Turkey’s foreign policy in shambles, but would also damage Turkey’s process of consolidating its democracy.

Supporting al-Assad’s stay in power after having called for Mubarak in Egypt and Gadhafi in Libya to step down would be committing political suicide for Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan both in terms of the region and the nation. Following the Baath dictatorship for Erdoğan, who emerged strong out of difficulties in the form of imprisonment, attempts to shut down the party and attempts at character assassination, would clearly be unimaginable. Had Erdoğan supported the Baath regime or had he remained a spectator, as the opposition demanded, it would have taken him only months to do the political harm to himself that his adversaries could in decades.![]()