The latest of Turkey’s countless attempts at a new Constitution has, as of November 2013, failed to reach fruition. The parliamentarian committee on drafting of the new Constitution, which was formed right after the 2012 elections, has been formally dissolved. This tragic end had been anticipated since the beginning of this year. Erdoğan’s main opposition, with provocations that the Justice and Development Party (AK Party) “had no intention of drafting a new Constitution,” only extended the life of the committee for a year. The question is why the Parliament which, in theory, represents all segments of society, cannot produce a new Constitution?

First of all, there is the issue of methodology. Both the AK Party, with its more than 300 members in Parliament, and the BDP, with its 30 plus members, were represented equally in the committee.

Furthermore, all parties had to reconcile on any one article for it to be finalized. That is to say, each article had to be agreed upon unanimously by all political parties. This method, which appears to be a fair process on the surface, was, in effect, the easiest way to guarantee not producing a Constitution.

In other words, any one political party had the right to veto any article with which it did not agree, rendering the votes of the other three parties powerless. This method effectively prevented the actual articles at stake from even making it to the committee’s agenda.

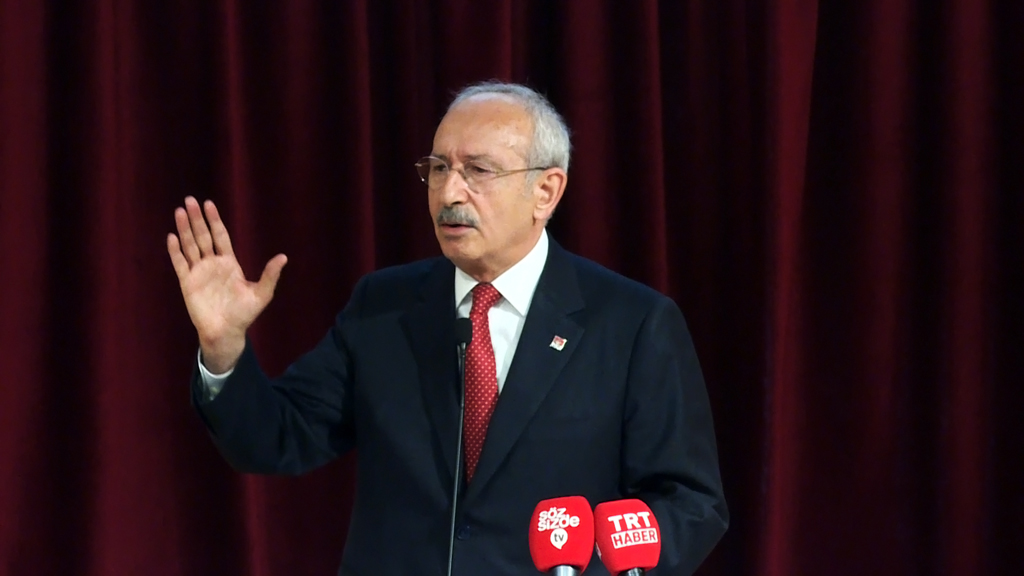

The other difficulty with the committee was that its constituting groups held irreconcilably different views on articles that were supposed to serve as the foundation of the social contract. The main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) is a party that has defined itself by the very problematic articles that needed to be changed. The most tendentious articles of the post-coup Constitution of 1980, namely, laicism and nationalism, are the very articles CHP accepts as its main principles. In other words, for the CHP a new Constitution would mean a transformation of the ideological ground upon which it had built itself. The conundrum for the CHP is that a new Constitution will necessarily mean a new CHP. The CHP had already announced that the articles that related to the relations of the citizen and the state, the military and the civilian, religion and the state constituted its red lines, even before CHP representatives joined the committee. The project of drafting a new Constitution without changing these very articles was doomed from the start.

The other opposition party in the committee is the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), which defines itself on the principle of nationalism. The MHP’s ideology and political strategies are, to a great extent, grounded on ethnicity, on the basis of which all state-citizen relations are imagined. As far as the MHP is concerned, the emphasis on Turkishness should be the focal point for all political discourse. As such, for the MHP, not unlike the CHP, a new and more democratic Constitution would necessarily be at odds with its political vision. The Peace and Democracy Party (BDP), which should in essence function as the antidote to the MHP’s vision, displays a vision that only focuses on the Kurdish issue. The tragedy is that, aside from a few utopian demands, the BDP’s demands could actually contribute to the drafting of a democratic Constitution.

The AK Party was struggling to find a mid-way amid the red lines drawn by the three opposition parties. If getting rid of the Jacobean articles of the junta Constitution was not possible, then at least considerable effort was going to be exerted to subdue the emphasis on ethnicity in those articles. This was an exercise in futility. The attempt of the 2013 draft Constitution was condemned to remain a bitter experience, both in terms of political parties and methodology. The hope for a new Constitution has been adjourned, yet again, u