As progress is made in the solution of the Kurdish issue and the disarmament of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), the most difficult case for the current political positions to tackle with will be the preservation of the status quo. As the solution process is rapidly internalized by the society, it cleared the way for the elites to go through a quite costly transformation period. The actors of the process, in particular, and political parties are having difficulty to manage the change in progress. The ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party) is, without a doubt, the most prepared one among the political parties. The reason is rooted in Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s being the leading actor of the 2009 initiative process as much as in the AK Party’s political identity and Erdogan’s political engineering skills. Although the AK Party could not reach its specific goals in the 2009 process, it has helped the party grassroots, in general, and the elites to quickly digest a transformation which could have endured for years in resolving the Kurdish issue. From this aspect, the 2009 initiative has become the preamble of the AK Party’s 2013 solution process. Similarly, all actors who played a negative role in the 2009 solution process are in trouble today, explicitly or implicitly.

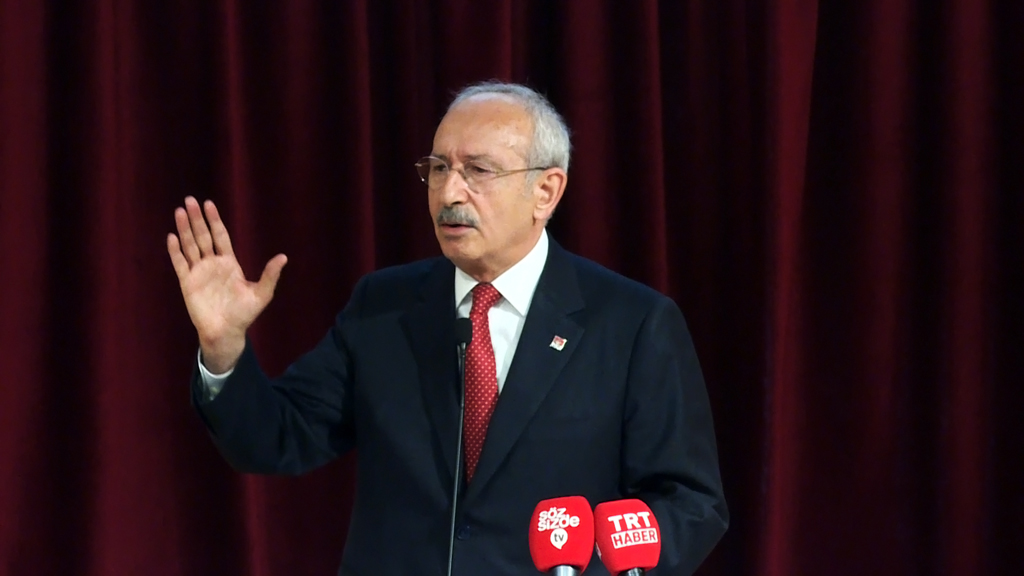

KILICDAROGLU’S DEMIREL-BAYKAL JUNCTURE

Actors of the Republican People’s Party (CHP), the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), the pro-Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party (BDP) and the PKK who did poorly in the 2009 initiative process have to make existentialist decisions in the 2013 solution process. The CHP will face the most difficult test along the way for having presumably quite different cliques inside the party. Claimed to be “a new party” at the rhetoric level, the CHP under the leadership of Kilicdaroglu will have to decide whether or not it is “a new party” in reality. In one way, the CHP, as the “oldest-newest” party of Turkey, cannot possibly handle the solution process. Names that are included in the party administration and that are considered as the new faces of the party do not represent the CHP grassroots. Moreover, it goes without saying that the support provided by the CHP grassroots to the solution process will not be sufficient to keep the new faces above the water line.

This has nothing to do with the different voices being heard in the CHP for the last few months. The “new CHP” discourse, which was to surface during the 2010 referendum vote and before the “new Turkey” discussions began, invested all it had in the “old Turkey;” therefore, contradicted itself. The spirit of the CHP’s immutable politics substantially emanated from the “say no” campaign during the referendum in which Kilicdaroglu sought shelter on the pretext of strengthening his leadership. The CHP protects the spirit of 2010 in the current issues, such as the right of defense in mother tongue, the judiciary packages and the 2013 solution process. As the solution process bears fruit, the CHP is destined to experience the administrative crisis at a deeper level and to lose the party grassroots to the MHP. If Kilicdaroglu does not act like “Suleyman Demirel,” the former President and the Justice Party leader who remained in the seat for quite some time, and if he adopts a politics solely to remain in the leadership seat, the Kemalist line spreading among the grassroots rightfully will increase pressures on Kilicdaroglu and ask him to be like “Deniz Baykal,” the previous CHP leader.

THE MHP’S DEAD-END

The MHP, in a way, is the barometer of the old-Turkey. In this regard, normalization of Turkey and the calm-down in the old-Turkey discussions are directly proportional to the MHP’s losing grass roots support. We witness heated discussions for a Turkey which is to be normalized in the middle-run through the solution process. Until the solution p