As the Middle East continues to be dominated by age-old rivalries, unresolved conflicts and protracted ethno-sectarian traumas, the epicenter of global hegemonic competition has shifted to the Asia-Pacific, where China and the U.S. are involved in a multipronged struggle for political, economic and geostrategic domination. In this context, tensions triggered by the launch of the Chinese-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) to fund large-scale infrastructure investments across Asia without political conditionality represents the last embodiment of a hard and soft power battle for politico-economic dominance in the Asia-Pacific. The unveiling of the AIIB with an initial capital base of $50 billion instigated intense controversy and diplomatic wrangling among Washington, Tokyo and Beijing, as Asia already has a multilateral lender in the form of the Japanese-dominated Asian Development Bank (ADB), which has a capital base of $160 billion, and the World Bank with $223 billion. The formal Chinese justification for the AIIB claims that structural reforms for more inclusive governance of the global financial system have stagnated and the infrastructure demands of Asian countries have gone beyond the capabilities of the World Bank and the ADB.

But the fact of the matter is China holds comparatively little influence over the ADB, World Bank or the International Monetary Fund (IMF) compared to Japan and the U.S., which is frustrating for the world's second largest economy. Controlling a multilateral investment bank will give Beijing greater influence over the Asia-Pacific region that needs a whopping $8 trillion-worth of infrastructure investment until 2020 to keep pace with global technological and demographic changes. China is understandably frustrated with the glacial pace of global governance reform, i.e. quota and voting rights in the IMF, which have been delayed for years. Likewise, despite the geometric expansion of the Chinese economy, the ADB is still dominated by Japan, which enjoys a permanent Presidency and double the voting rights of China. The same sense of frustration on the Chinese side was visible during the foundation of the New Development Bank established by the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa).

From another angle, China's initiative in launching the AIIB represents a direct response to the U.S.-led project of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which was presented as a form of multilateral regional integration, but perceived as strengthening bilateral military alliances and economic partnerships in Asia by excluding China. The attempted regional reordering at the expense of Beijing has sparked an immediate reaction by China, which kick-started negotiations for Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with the members of ASEAN. Along with Xi Jinping's grand geostrategic vision, including the New Silk Road, Maritime Silk Road, and Air Defense Identification Zone, the AIIB Project perfectly reflects the symbiosis between China's soft and hard power considerations aimed at recasting the region's strategic landscape around China.

Although the AIIB will be officially launched later in 2015, so far 57 countries have joined as founding members including Turkey, India, Iran, Israel, France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, the U.K., Russia, Saudi Arabia, Australia and South Korea. The U.S., which so far has tried to lobby its allies against the initiative with limited success, seems to stand alone in the opposition camp. The Obama administration used the absence of transparent governance standards and competition with the World Bank and ADB as an unconvincing excuse, while critics see the U.S.'s decision not to join as a strategic mistake for future investment opportunities as allies have jumped on the bandwagon.

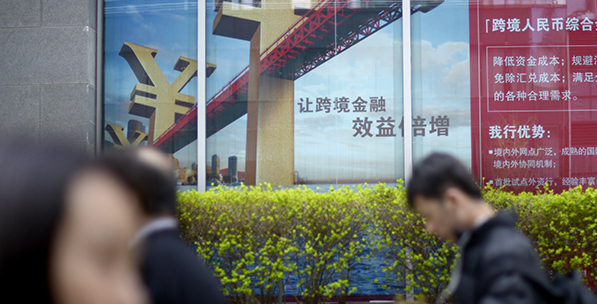

The widespread global acceptance of the AIIB in the face of U.S. opposition indicates a tectonic shift in the global economic order, given that one of the main functions of the AIIB will be to facilitate the internationalization of the Chinese currency - the Ren