“Saving Egypt from the coming destruction will not happen without the unity of the army and the people, the formation of a national salvation front consisting of political and military leaders, and the upholding an unequivocally civil state with military protection, exactly like the Turkish system … If this does not happen in the next few days, Egypt will fall and collapse, and we will regret [wasting] the days that remain before a new constitution is announced … The people’s peaceful protest is imperative and a national duty, until the army responds and announces its support for the people.”

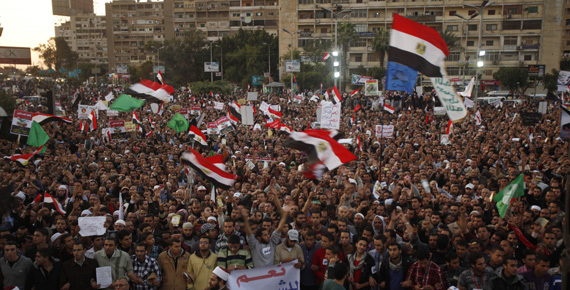

The above lines are taken from the front page of the daily newspaper, Al-Dustour, dated Aug. 11. This was how the “Are you aware of the danger?” campaign got started barely a month after the presidential elections, but the campaign that aimed to mobilize “one million people in Tahrir” against Morsi was not successful then. The origins of this campaign can be traced to earlier occasions. One of the most interesting of these was the publication of an article titled “An Arab Springtime,” soon after the revolution, in the Monthly Review journal belonging to a francophone Egyptian Samir Amin. The common ground that bound Amin’s article and Al-Dustour - despite their vast differences in quality and ideological stance - was their shared stance against Ikhwan (the Muslim Brotherhood).

Amin, who described Ikhwan as an apparatus created by the comprador bourgeoisie, “founded in 1927 by the English Embassy, developed by the Americans over the years, financed by the Saudis, supported both by Sadat and Mubarak,” did not even realize that he was talking about a gigantic conspiracy theory. At the end of his analysis, embellished by a little “Marxist political economy” and a little “leftist democratic discourse,” what he was really saying was that “nothing has changed in Egypt.”

Amin, in his article filled with words such as “reactionary,” “anti-democratic,” “against social progress,” “beards,” and “veils,” came close to suggesting that Sadat and Mubarak were really “Islamists.” All the issues signaled by Amin in his article were embodied in the form of a coalition between “felol” and the liberals over the last three weeks. This time we are hearing, mostly from the liberals’ voice, a different articulation of the same political position - the liberals are not really telling us anything about Egypt.

The main criticism against Morsi concerns his “majoritarian rule.” However, what is being experienced in Egypt right now is not “majoritarianism” but rather a struggle to “rule” under military-judiciary tutelage. Two quotes from Carl Schmitt might explain the situation in Egypt better. First, Schmitt said: “The sovereign is he who decides on the exception.” Morsi gained the power he was not able to attain even after having won the elections by actualizing a “state of exception.” Second, the liberals’ maximalist demands as the self-acclaimed source of truth has only served to prove Schmitt’s statement, “There is no liberal politics, [but] only a liberal critique of politics,” right too.