Another attempt of making a new constitution in Turkey, of which we lost the count, has once again remained inconclusive as of November 2013. Formed after the 2011 general elections, the Constitutional Reconciliation Commission was practically abrogated. In fact, this dramatic end was anticipated at the beginning of 2013.

The Commission’s term of duty was barely extended for about a year following Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s opposition and his pressure claiming: “You have no intention to make a new constitution.”

But why cannot the political parties representing all sects of the society make a new constitution? First of all, there is a methodological problem. In the Reconciliation Commission, the ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party) and the pro-Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party (BDP) have equal weights of votes (3 members for each party represented in the National Assembly regardless of the number of their representatives) although the AK Party has more than 300 parliamentary representatives against about 30 of the BDP.Besides, a unanimous yes vote (in the Commission) was required for the approval of each article (drafted in the Commission).

Namely, it was impossible to pass an article without reaching conciliation among all the parties. This seemingly egalitarian method of drafting a constitution is, in a way, the most guaranteed way of not being able to make a constitution. That is to say, if a political party does not wish to pass a particular article in the Constitutional Reconciliation Commission, (sufficiently, only one of) its commission member(s) votes “no”; therefore, it has the power to turn null the (yes) votes of other three political parties. In fact, this method prevented even the debates from taking place on the controversial articles in the Commission.

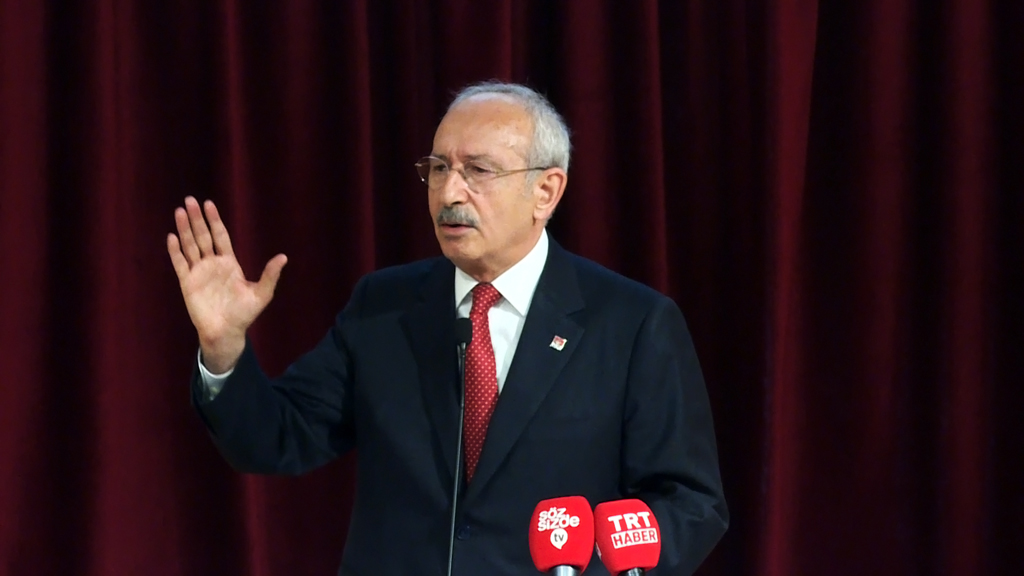

Another central issue was that the members of the Commission have completely different worldviews regarding the new Constitution which was to form the main text of the social contract. The Republican People’s Party (CHP) is a party that builds up its identity almost totally on the articles that need to be changed.

The secularism and leftist-nationalism, which the CHP reckons among its main principles, form the spirit of the Constitution written by the 1980 military coup executioners. In other words, a new Constitution for the CHP is to change its own fundamental ideological ground. Therefore, the issue of new Constitution for the CHP means, in a way, a new issue for the CHP. The CHP joined the Commission by announcing its “redlines” as the state-citizen, the military-civilian and the state-religion relations. It was impossible anyway to draft a new Constitution without making amendments in any of the (redlined) relevant articles.

Another opposition party in the Commission was the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) which forms its identity through nationalism. The ideology and politics of the MHP mostly rely on the ethnic ground that regulates the state-citizen relations in the Constitution.

At the center of its political discourse, the MHP emphasizes the “Turkishness” in the Constitution. Therefore, a new and democratic Constitution for the MHP, like the CHP, means exerting efforts on a worldview which is quite opposite to that of its own. As the antidote of the MHP, the BDP exhibits an approach with a focus on the Kurdish question only. If their some “utopic” demands are left aside, the BDP was also making demands to contribute to a democratic Constitution.

The AK Party was stuck among the red lines of these parties and trying to find a middle way. The efforts were exerted particularly in order to completely eliminate the Jacobian articles in the coup’s Constitution, if not possible, to clean them out of any ethnical emphasis. But unfortunately, this did not happen. The 2013 Constitution experience remained as a bitter experience both in terms of methodology and of political parties. Even