Back to top

Hakkı Uygur

Center for Iranian Studies (IRAM)

Similar demonstrations and protests have taken place in Iran in the past. This is not the first time. It is a situation that we encounter quite frequently. As we and others repeatedly stressed, there are very limited channels, through which democratic demands can be made. The path of democratic politics remains blocked. That, in turn, creates a fertile ground for popular demonstrations. In this regard, the allegations of election fraud, the price hikes, certain incidents that took place on university campuses and the most recent development, which wounded the public’s conscience, tend to cause people to take to the streets.

The protests have been underway for three weeks. In other words, they have continued for a significant amount of time. Although the level of mass participation remains low, we observe that the protest is spreading to additional areas and among new social groups. Most recently, we have seen university students being joined by high school students in this protest. Those are important developments. Obviously, even today, the state has the power and ability to crack down on this protest.

Another noteworthy development was Ali Khamenei’s speech, which was extremely dissatisfactory. Specifically, he almost repeated the speeches from ten years ago. He made accusations against the people on the street. Once again, he recalled that he had been in exile in Balochistan before the revolution and said that he loved the Baloch people. In other words, his political grasp appears to have weakened. It seemed interesting to me that he would compare the present situation with the conditions in Balochistan some fifty years ago. As such, it appeared that he was not fully aware of what was happening. Indeed, he repeated the all-too-familiar accusations. He claimed that the protestors had burned copies of the Qur’an and mosques. By contrast, the protestors had a very basic and simple reason [for protesting] and people are being killed on the streets still today. The number of deaths has allegedly nearest 100. That is a very significant development.

At this time, such mass reactions remain limited to the Kurdish region, but if the protest spreads to professional classes and leads to strikes, especially in Tehran and at petroleum production facilities, the situation is likely to deteriorate. After all, all the social groups and all the major sociological groups in Iran have major problems –as many have already written and stated. They have decades-old problems and people do not see any hope when they look into their future. That is why Iran is one of the worst-affected countries globally by brain drain. That is why approximately 10 percent of that country’s population lives abroad. If that lack of hope causes additional groups to take to the streets and unites them –especially if ordinary people, not just the professional opponents, some Kurdish organizations, the People’s Mojahedin Organization and action-prone college students, who are already on the streets, take to the streets– the situation will likely become more serious and the crowds will likely grow. The situation could then spin out of control. I do not, however, believe that the administration is capable of showing any kind of flexibility. That was the takeaway from Khamenei’s address. He seemed utterly unwilling to appreciate the problem. That is why I believe that the government will keep cracking down [on the protest] the same way.

Back to top

Hakkı Uygur

Center for Iranian Studies (IRAM)

Similar demonstrations and protests have taken place in Iran in the past. This is not the first time. It is a situation that we encounter quite frequently. As we and others repeatedly stressed, there are very limited channels, through which democratic demands can be made. The path of democratic politics remains blocked. That, in turn, creates a fertile ground for popular demonstrations. In this regard, the allegations of election fraud, the price hikes, certain incidents that took place on university campuses and the most recent development, which wounded the public’s conscience, tend to cause people to take to the streets.

The protests have been underway for three weeks. In other words, they have continued for a significant amount of time. Although the level of mass participation remains low, we observe that the protest is spreading to additional areas and among new social groups. Most recently, we have seen university students being joined by high school students in this protest. Those are important developments. Obviously, even today, the state has the power and ability to crack down on this protest.

Another noteworthy development was Ali Khamenei’s speech, which was extremely dissatisfactory. Specifically, he almost repeated the speeches from ten years ago. He made accusations against the people on the street. Once again, he recalled that he had been in exile in Balochistan before the revolution and said that he loved the Baloch people. In other words, his political grasp appears to have weakened. It seemed interesting to me that he would compare the present situation with the conditions in Balochistan some fifty years ago. As such, it appeared that he was not fully aware of what was happening. Indeed, he repeated the all-too-familiar accusations. He claimed that the protestors had burned copies of the Qur’an and mosques. By contrast, the protestors had a very basic and simple reason [for protesting] and people are being killed on the streets still today. The number of deaths has allegedly nearest 100. That is a very significant development.

At this time, such mass reactions remain limited to the Kurdish region, but if the protest spreads to professional classes and leads to strikes, especially in Tehran and at petroleum production facilities, the situation is likely to deteriorate. After all, all the social groups and all the major sociological groups in Iran have major problems –as many have already written and stated. They have decades-old problems and people do not see any hope when they look into their future. That is why Iran is one of the worst-affected countries globally by brain drain. That is why approximately 10 percent of that country’s population lives abroad. If that lack of hope causes additional groups to take to the streets and unites them –especially if ordinary people, not just the professional opponents, some Kurdish organizations, the People’s Mojahedin Organization and action-prone college students, who are already on the streets, take to the streets– the situation will likely become more serious and the crowds will likely grow. The situation could then spin out of control. I do not, however, believe that the administration is capable of showing any kind of flexibility. That was the takeaway from Khamenei’s address. He seemed utterly unwilling to appreciate the problem. That is why I believe that the government will keep cracking down [on the protest] the same way.

Back to top

Pouya Alimagham

History-Massachusetts Institute of Technology

On September 13, 2022, the “morality police” arrested Mahsa Amini for “inappropriately” wearing her head covering. Her detainment and subsequent death three days later –no doubt resulting from her arrest– sparked the latest round of anti-government protests. The point that is missing from much of the discussion around her arrest, however, is what that “inappropriate” head covering symbolizes to the state.

Ostensibly, the point of the state mandated hijab is the foster a “moral society” through such prescribed modest dress. There is a dress code for men and women, but it is especially onerous for women. The problem is that in Iran, as elsewhere, women do not want to be regulated about matters related to their bodies. Consequently, many women wear their head covering in a manner that not only subverts the mandated dress code, but also signals a form of defiance of the state.

That is, women are wearing their politics on their proverbial sleeves, and the state knows this is happening and understands the political statement being made via one’s attire. As such, Amini’s arrest has a political feel to it; she was likely profiled as being not only in violation of the dress code but also in political opposition to state.

It is these aspects of her detainment and death that resonates with protesters to mean that the protests are not merely about objecting to the dress code but demonstrating against the state that takes it upon itself to mandate and enforce such dress codes in the first place – and everything else for which the state has failed miserably.

In other words, the protests are about much more than just the mandatory hijab, but also encompass larger political grievances, such as gender inequality, corruption, economic mismanagement, spiraling inflation, transparency, and accountability, political repression, and the overall securitization of the country. It is these issues that serve as a tie that binds these protests with its antecedents in 2019, 2017-2018, 2009, and before.

Back to top

Pouya Alimagham

History-Massachusetts Institute of Technology

On September 13, 2022, the “morality police” arrested Mahsa Amini for “inappropriately” wearing her head covering. Her detainment and subsequent death three days later –no doubt resulting from her arrest– sparked the latest round of anti-government protests. The point that is missing from much of the discussion around her arrest, however, is what that “inappropriate” head covering symbolizes to the state.

Ostensibly, the point of the state mandated hijab is the foster a “moral society” through such prescribed modest dress. There is a dress code for men and women, but it is especially onerous for women. The problem is that in Iran, as elsewhere, women do not want to be regulated about matters related to their bodies. Consequently, many women wear their head covering in a manner that not only subverts the mandated dress code, but also signals a form of defiance of the state.

That is, women are wearing their politics on their proverbial sleeves, and the state knows this is happening and understands the political statement being made via one’s attire. As such, Amini’s arrest has a political feel to it; she was likely profiled as being not only in violation of the dress code but also in political opposition to state.

It is these aspects of her detainment and death that resonates with protesters to mean that the protests are not merely about objecting to the dress code but demonstrating against the state that takes it upon itself to mandate and enforce such dress codes in the first place – and everything else for which the state has failed miserably.

In other words, the protests are about much more than just the mandatory hijab, but also encompass larger political grievances, such as gender inequality, corruption, economic mismanagement, spiraling inflation, transparency, and accountability, political repression, and the overall securitization of the country. It is these issues that serve as a tie that binds these protests with its antecedents in 2019, 2017-2018, 2009, and before.

Back to top

İsmail Sarı

Ankara Hacı Bayram Veli University & ORSAM

It is possible to view the most recent protests in Iran, which started on 16 September over Mahsa Amini’s death, as a struggle against various forms of oppression that coincide on the basis of gender, religion and ethnic background. The protests, whose main message has been “woman, life, liberty” managed to attract university students despite threats from the officials. What was most surprising, however, has been the role and leadership of women in those protests. After all, there were a very limited number of intellectuals that thought the Iranian women capable of playing such a role in Iran’s future. That is because women have faced more oppression than any other group under the current regime –even though Kurds and other ethnic minorities as well as Sunnis and others are certainly under pressure, too– and they have grievances. They encounter patriarchal domination on a daily basis. The protest initially erupted in Iran’s Kurdish provinces since Amini was a woman of Kurdish origin. It proceeded to spread to Tehran, Hamadan and Mashhad. Later, albeit surprisingly, there were demonstrations in Qom, which is considered the heart of the regime. Whereas the regime would like to view those social movements as a plot by domestic and foreign enemies of the state, who wish to exploit Amini’s death, hardly anyone is unaware of the long-standing sociological tensions, the people’s unhappiness and the shrinking of the political arena in Iran. In this regard, the latest explosion merely awaited a trigger. That trigger turned out to be Mahsa Amini. The Iranian administration could have kept the reaction under control by expressing its sadness over the death of a 22-year-old woman instead of adopting a defensive stance. In truth, that reaction signalled that the regime, too, has been losing touch with the population. My point is that Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader, could have prevented the death of dozens of people during the protests by saying that he shared the pain of Mahsa Amini’s family rather than sending his representative to that family. He did not, however, take that step because the regime believes that it can control the people by exerting pressure – just like all other authoritarian regimes.

Perhaps the question, which one must ask today, is what distinguished the current protest from what happened four years ago. As Sadegh Zibakalam, a renowned Iranian intellectual, maintains, there are several radical differences between the most recent demonstrations and the previous protests. The first point is that the current protests are quite widespread and, unlike in the past, erupted in major cities like Tehran, Isfahan and Shiraz as well. The second point is the level of participation among young people and the third point is the leadership role that Iranian girls have assumed. The December 2018 protests, which started in Mashhad over corruption, the rising cost of living and unemployment before spreading to the countryside, and the November 2019 protests over the increase in fuel prices, which occurred in Ahvaz, Khorramshahr, Birjand, Mashhad, Gachsaran, Sirjan, Bandar Abbas, Isfahan and Shiraz, were similar in nature and ended quickly without evolving into mass movements. It seems that the “pursuit of liberty” represents a much stronger force in mobilizing the masses in Iran than economic problems. Moreover, Mahsa Amini’s death wounded the public’s conscience and cause the anger, which the masses had accumulated toward the regime, to be unleash onto the streets. What we notice in this protest is a resistance by young people –especially women. It is necessary to view the resistance against the security forces as a resistance against the regime itself, because the young generation does not want to keep silent anymore.

Back to top

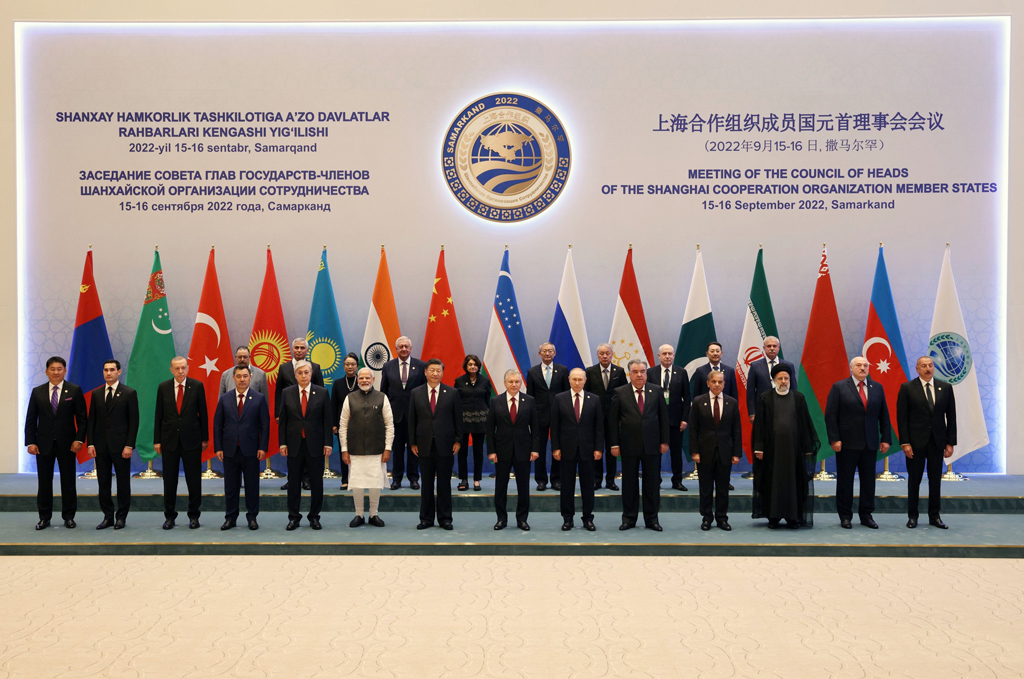

İsmail Sarı

Ankara Hacı Bayram Veli University & ORSAM

It is possible to view the most recent protests in Iran, which started on 16 September over Mahsa Amini’s death, as a struggle against various forms of oppression that coincide on the basis of gender, religion and ethnic background. The protests, whose main message has been “woman, life, liberty” managed to attract university students despite threats from the officials. What was most surprising, however, has been the role and leadership of women in those protests. After all, there were a very limited number of intellectuals that thought the Iranian women capable of playing such a role in Iran’s future. That is because women have faced more oppression than any other group under the current regime –even though Kurds and other ethnic minorities as well as Sunnis and others are certainly under pressure, too– and they have grievances. They encounter patriarchal domination on a daily basis. The protest initially erupted in Iran’s Kurdish provinces since Amini was a woman of Kurdish origin. It proceeded to spread to Tehran, Hamadan and Mashhad. Later, albeit surprisingly, there were demonstrations in Qom, which is considered the heart of the regime. Whereas the regime would like to view those social movements as a plot by domestic and foreign enemies of the state, who wish to exploit Amini’s death, hardly anyone is unaware of the long-standing sociological tensions, the people’s unhappiness and the shrinking of the political arena in Iran. In this regard, the latest explosion merely awaited a trigger. That trigger turned out to be Mahsa Amini. The Iranian administration could have kept the reaction under control by expressing its sadness over the death of a 22-year-old woman instead of adopting a defensive stance. In truth, that reaction signalled that the regime, too, has been losing touch with the population. My point is that Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader, could have prevented the death of dozens of people during the protests by saying that he shared the pain of Mahsa Amini’s family rather than sending his representative to that family. He did not, however, take that step because the regime believes that it can control the people by exerting pressure – just like all other authoritarian regimes.

Perhaps the question, which one must ask today, is what distinguished the current protest from what happened four years ago. As Sadegh Zibakalam, a renowned Iranian intellectual, maintains, there are several radical differences between the most recent demonstrations and the previous protests. The first point is that the current protests are quite widespread and, unlike in the past, erupted in major cities like Tehran, Isfahan and Shiraz as well. The second point is the level of participation among young people and the third point is the leadership role that Iranian girls have assumed. The December 2018 protests, which started in Mashhad over corruption, the rising cost of living and unemployment before spreading to the countryside, and the November 2019 protests over the increase in fuel prices, which occurred in Ahvaz, Khorramshahr, Birjand, Mashhad, Gachsaran, Sirjan, Bandar Abbas, Isfahan and Shiraz, were similar in nature and ended quickly without evolving into mass movements. It seems that the “pursuit of liberty” represents a much stronger force in mobilizing the masses in Iran than economic problems. Moreover, Mahsa Amini’s death wounded the public’s conscience and cause the anger, which the masses had accumulated toward the regime, to be unleash onto the streets. What we notice in this protest is a resistance by young people –especially women. It is necessary to view the resistance against the security forces as a resistance against the regime itself, because the young generation does not want to keep silent anymore.

Back to top

Back to top

Serhan Afacan

Institute of Middle East and Islamic Countries-Marmara University

The Iranian government refuses to show the kind of flexibility, which it demonstrated in negotiations with the United States, with which it has hostile relations, for many years, to a growing part of its population regarding their demands. Meanwhile, there is anger increasingly brewing in the country over the failure to address the long-standing demands of various groups vis-à-vis political participation, transparency in government and cultural rights. Furthermore, whereas the rising cost of living, which has become a chronic problem in the country, fuels society’s anger, economic hardship is not the sole source of popular complaints. Although the young generations have lowered their economic expectations in Iran, as their peers did in many parts of the world, they refuse to accept the narrowing down of the domain of rights and liberties. Naturally, the dominant political structure itself is directly involved in that issue. As the demonstrations, which started in the wake of Mahsa Amini’s death in the custody of the morality police, clearly show, protests tend to erupt for any given reason and quickly reach a certain point, where they target the regime. Although the protests will lose their momentum due to their lack of leadership (just like past protests) due to the nature of that country’s political system and because the authorities will take all necessary precautions to prevent the protestors from organizing, the popular rage will continue to accumulate. After all, the main problem in Iran is rooted in legal arrangements, starting with the Constitution. As such, a limited opening is unlikely to address that problem permanently.

The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran entered into force in 1979 and was amended just once, in 1989, to make the administrative structure more functional. Over the years, the Constitution faced criticism for its narrow interpretation, which did not allow popular demands to be taken into consideration, and the implementation of the Islamic Penal Code. The country’s morality police remains one of the mechanisms for the implementation of that law. Whereas the mandatory use of hijab has been enforced in Iran with leniency in practice for a long time, the case of Mahsa Amini demonstrated how the morality police as well as certain institutions, such as the Institution for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice and the Basij organization, can engage in oppressive behavior. That is why a limited opening unlikely to yield long-term results in Iran, where legal arrangements will have to be made sooner or later. How that step could be taken whilst preserving the Islamic nature of that country’s regime, however, remains an important question for the reformists as well as the conservatives, who actually have the power. The Iranian people will continue to double down on their demands on the streets unless and until the right method is identified to achieve that result.

Back to top

Serhan Afacan

Institute of Middle East and Islamic Countries-Marmara University

The Iranian government refuses to show the kind of flexibility, which it demonstrated in negotiations with the United States, with which it has hostile relations, for many years, to a growing part of its population regarding their demands. Meanwhile, there is anger increasingly brewing in the country over the failure to address the long-standing demands of various groups vis-à-vis political participation, transparency in government and cultural rights. Furthermore, whereas the rising cost of living, which has become a chronic problem in the country, fuels society’s anger, economic hardship is not the sole source of popular complaints. Although the young generations have lowered their economic expectations in Iran, as their peers did in many parts of the world, they refuse to accept the narrowing down of the domain of rights and liberties. Naturally, the dominant political structure itself is directly involved in that issue. As the demonstrations, which started in the wake of Mahsa Amini’s death in the custody of the morality police, clearly show, protests tend to erupt for any given reason and quickly reach a certain point, where they target the regime. Although the protests will lose their momentum due to their lack of leadership (just like past protests) due to the nature of that country’s political system and because the authorities will take all necessary precautions to prevent the protestors from organizing, the popular rage will continue to accumulate. After all, the main problem in Iran is rooted in legal arrangements, starting with the Constitution. As such, a limited opening is unlikely to address that problem permanently.

The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran entered into force in 1979 and was amended just once, in 1989, to make the administrative structure more functional. Over the years, the Constitution faced criticism for its narrow interpretation, which did not allow popular demands to be taken into consideration, and the implementation of the Islamic Penal Code. The country’s morality police remains one of the mechanisms for the implementation of that law. Whereas the mandatory use of hijab has been enforced in Iran with leniency in practice for a long time, the case of Mahsa Amini demonstrated how the morality police as well as certain institutions, such as the Institution for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice and the Basij organization, can engage in oppressive behavior. That is why a limited opening unlikely to yield long-term results in Iran, where legal arrangements will have to be made sooner or later. How that step could be taken whilst preserving the Islamic nature of that country’s regime, however, remains an important question for the reformists as well as the conservatives, who actually have the power. The Iranian people will continue to double down on their demands on the streets unless and until the right method is identified to achieve that result.

Back to top