Turkey is at a turning point. Under the Justice and Development Party (AKP) incumbency, the country has been transforming. The AKP’s progressive policies have carried the side effect of making the country’s fault lines overt. Political dissent that has been publicly on display is the manifestation of this side effect. The material conditions for a solution are already being formed in Turkey. Any analysis of these protests should be able to transform political dissent into a concrete policy that takes different popular dynamics into account. The political future of the ruling AKP and the opposition is at a cross-roads.

HOW DID THE PROTESTS DEVELOP?

What began as an outcry against a local project in Istanbul has snowballed into widespread anger against the Turkish government. Protests began in Gezi Park on May 27, 2013, when approximately sixty protesters reacted to an ongoing construction plan that was misunderstood by demonstrators. According to Kadir Topbaş, mayor of Istanbul, the work was neither about the building of a shopping mall, nor the demolition of the park, but about the displacement of trees. The plan was announced to the public after demonstrations over the protection of a park turned into a movement against the Turkish prime minister and the AKP government. What was perceived as a heavy-handed response by the police has intensified the rage of street clashes. Consequently, unrest has spread all over the country.

During the second week of protests, demonstrations protecting trees or the park itself developed into a social breakdown. It is important to focus on the sociological aspects of the protests in order to be prepared for the long-term consequences of such a breakdown. Therefore, we need to analyse who the protesters are and what they are asking for.

THE GENERAL ATMOSPHERE OF THE PROTESTS

The social aspect of the protests is a lot clearer than its political side. Protesters consist of people from different backgrounds and ideologies. Practically, the protesters can be categorized under three different layers that do not share a common ground under normal conditions. What binds these protesters together are their anti-Erdogan stance and their reaction to the excessive use of force by police at the start of the demonstrations. Therefore, their alliance is temporal.

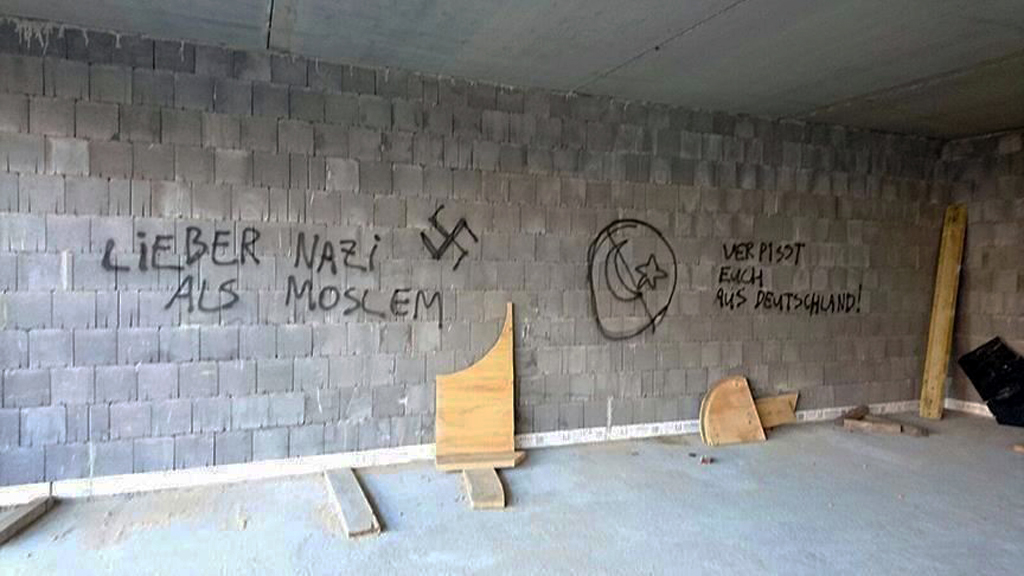

The common ground for these protests is the rising fear and ignorance of some groups in Turkey due to the polarized structures of society that are Alevi-Sunni, Islamist-secularist, and Turk-Kurd. The AKP symbolizes the Sunni, Islamist, and Turkish side of this bipolar structure that creates the feeling of defeat and despair for other camps. The main reason for this feeling is the failure of the opposition to represent the voice of the masses in Turkey.

In a political system like Turkey's, the prime minister of a country does not directly communicate with the masses as there are intermediate mechanisms like professional bodies, trade unions, and various NGOs that function as the voice of the people. In Turkey, those mechanisms do not function properly and people feel the necessity to express themselves on the streets. The dissent should not be interpreted as a list of demands regarding the political system, but rather as the expression of the protesters’ rejections of the increasing intervention into their lifestyle.

It is also noteworthy to mention the previous month's political developments in Turkey in order to have a better understanding of what has been happening. It is clear that protesters have a feeling of despair, precipitated by a decade of AKP rule. The recent political unrest should be seen as the last brick on the wall. The Turkish government passed a law regulating the sale hours of alcohol, which is common practice in the United States and in Europe.

However, unlike those western countries, intervention regarding alcohol sales in Turkey has sociological connotations that were overlooked by the government. Due to the intensification of a po