The year 2011 was going to be a year in which the political and social effects of the September 12, 2010 referendum for drafting of the new constitution would be felt. As Turkey bid farewell to its old political habits with the September 12 referendum, a public debate on how new political structures were going to be built began. The focus of the debate was “innovation”. As the public debate was gearing towards an exhaustive examination of the new political patterns, the wave of revolution and transformation that began in Tunisia and spread over the entire region took the public discourse hostage. Turkey’s discussions of ‘innovation’ were absorbed in the wave of transformation. Turkey faced the Arab Spring as a country that has demonstrated significant developments in its own political transformation. Political actors, who had not contributed to the ongoing efforts of democratization in Turkey satisfactorily, especially in the context of the Kurdish question, tried, to no avail, cast themselves in important roles in the uprisings in the region.

In 2011, the incumbent Justice and Development Party (AK Party) was going to campaign for its third term in power after having won the vote of confidence in the referendum on September 12, with a high margin of 58 percent. In the aftermath of the referendum, the main opposition CHP (Republican People’s Party) after its contentious change of leadership; BDP (Peace and Democracy Party) after its decision to boycott the referendum and the democratic initiative; and MHP (National Movement Party) after its constituents’ reaction to its stance on the Kurdish initiative reflected to the poles in the referendum, embarked on the electoral process with ambitions of their own. Contrary to the attitudes of the opposition, the interim elections resulted in AK Party’s landslide victory.

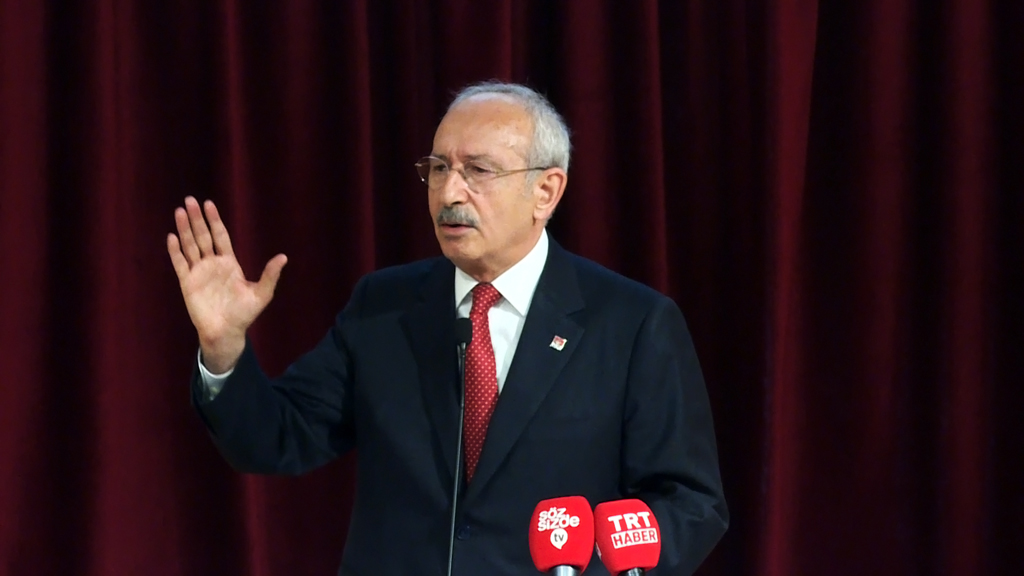

The elections of June 12th, which can be considered the most important event of the year 2011, affected the opposition parties in different ways. Internal strife in the main opposition party CHP stretched through the entire year. CHP had still not stabilized after its contentious change of leadership when it entered the electoral process. The new party leader, Kemal Kılıcdaroglu joined the “new Turkey” discourse with his vision of a “new CHP”. Kılıcdaroglu’s vision for the party satisfied neither its lifetime constituents, nor those who expected an AK Party like performance from CHP. This inevitably caused factions within the party. In the fall of 2011, after Prime Minister Erdogan apologized for Dersim events in the name of the state, CHP found itself paying for the sins committed during the single party regime. It became clear for the new vision of CHP to take hold, it needed a clean break from its treacherous past. The MHP campaign kicked off under pressure for having witnessed that the party’s strong opposition against sensitive issues such as the Kurdish Initiative, the Kurdish Question’s peaceful resolution, and the September 2010 referendum did not attract popular support. Notwithstanding its internal bickering, MHP during this year failed to demonstrate a definitive line or stance, and the main political target of the party became achieving the 10 percent national threshold required to qualify for the parliament.

Finally, the pro-Kurdish BDP entered the race with heated discussions and a wind of change. Applying their previously-agreed ‘umbrella party’ concept through their endorsement of independent candidates from different ba