If we searched for the most striking and concise way to describe the Egyptian political system, “military-judiciary complex” would be one of the most appropriate definitions. Mohammed Morsi has not only become the fifth president of Egypt after the 29 years and 120 days long Mubarak presidency, but has also triggered the process in which all regional dynamics and balances would change. The established order in Egypt for the last half a century survived in the “political sphere” created by the both the regional “regional order” and the “iron fist” government in the country. The Egyptian establishment had believed that the Egyptian leg of the Arab uprisings would have come to the end of its bio-political life once Mubarak was sacrificed. Mubarak would step down, and the established order would continue to hold its share of power.

It is possible to say that the Egyptian military regime, despite having been shocked in the elections when the Freedom and Justice and Al-Nour parties gained the crushing majority in the parliament, has managed to remain cool and composed. The wisdom of this composure became clear later on. The SCAF, not really paying any heed to the existence of a parliament considered presidency as the office that would determine its survival. The Egyptian tutelary regime, in an unexplainable move, dismissed the constitutional commission with an administrative court decision right before the elections. More radical followed. The parliament was disbanded with a mini coup, and the president’s authorities were limited.

The elections following all these interventions were held between what Egyptians liked to call 'fouloul' referring to the remnants of the old regime and “new Egypt’. Morsi has become the president of 'fouloul bureaucracy' after having beaten “fouloul” in the elections. Incumbent Morsi took steps that could be considered revolutionary despite the harsh opposition posed by the Egyptian tutelary regime. Particularly, his dismissal of Tantawi and the head of intelligence Murad Muwafy in his effort to end the military tutelage were historically important moves for Egypt. Morsi’s swift performance in the beginning of his administration has raised the bar of expectations unnecessarily.

However, the established order in Egypt was waiting for the Morsi administration on the defensive with all its weight. In the final analysis, Morsi, for the majority of the Egyptian bureacracy, was no one but the leader that had beaten Ahmad Shafik in the elections. It did not take long for the Supreme Constitutional Court of Egypt (SCC)—the Egyptian version of the military-judiciary complex—to make its appearance on the stage. Thus, with the pressure from the SCC, the controversial prosecutor general of Egypt, Abdelmeguid Mahmoud, was able to keep his position despite having been reappointed by Morsi as Egypt’s ambassador to Vatican. It was only expected that Morsi, who did not encounter much trouble with the military tutelage that lacked ideology, would enter a harsh struggle with the bureaucracy and judiciary, which carries both ideological and social stance.

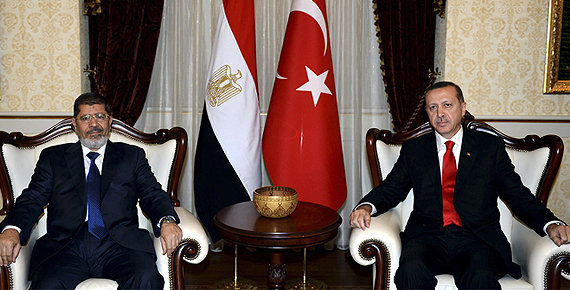

The Potential of Turkish Egyptian Collaboration

It is possible to match all analyses that could be drawn from Egypt’s last two years with the various manifestations of tutelage in Turkey in the last five decades. If Turkey and Egypt, who have rediscovered each other after a century long gap, post-Mubarak, could form an axis, they will have taken a step that could deeply influence geopolitics in the whole region.

The indicators of the future dynamics of Turkish-Egyptian relations were revealed when Morsi attended the JDP convention. It is possible for Turkey, the only country that has carried out official visits at the level of the ministers, deputy Prime Minister, prime minister and the president, to achieve a strategical outlook in its relations with Cairo. Can we infer a strategical axis from Erdogan’s agen