Turkey's presidential candidates introduced their vision documents last week to mark a turning point in the campaign season. We now have a better idea about each contender's platform, campaign themes, take on domestic and foreign policy and what meaning they attribute to the office of the president.

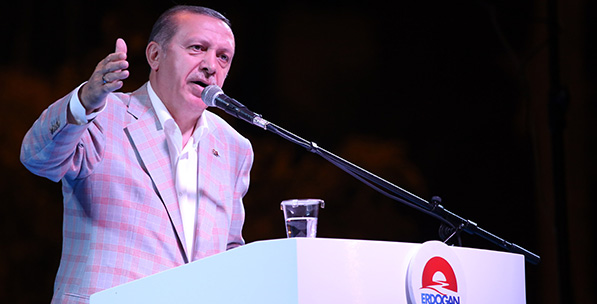

The events where Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and opposition candidate Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu demonstrated their respective visions with greater clarity than before show just how uneven the top two contenders are. Ever since securing the nomination, İhsanoğlu has left opposition voters looking for an excuse to embrace him to no avail. Each day ends with disappointment and a desperate wait for a miracle. İhsanoğlu, whose sponsors fielded him as the complete opposite and antidote to Erdoğan, simply failed to impress. As a matter of fact, a sizeable chunk of the electorate was eager to endorse the man but gave up after last week's event. In this sense, the most recent developments signaled that Erdoğan will further widen the margin of victory until election day. To be fair, a number of observers, including myself, had predicted such an outcome as soon as the Republican People's Party (CHP) and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) announced İhsanoğlu's candidacy. The period between İhsanoğlu's formal announcement and the present worked to the candidate's disadvantage.

A series of opinion polls have since established that hardly 60 percent of CHP and MHP voters consider going to the polls on Aug. 10 to vote for their designated candidate. Unless the opposition parties can perform a miracle before election day, all signs point to a first-round victory for Erdoğan and suggest that İhsanoğlu's campaign will fail to meet their expectations. The actual issue here, though, is not İhsanoğlu's likely defeat. A simple quantitative and political analysis could predict a slim chance of victory for any candidate endorsed by the CHP and MHP. The real problem, instead, is the disappointment and sense of disenchantment, hopelessness and distrust of the political process that İhsanoğlu and, by extension, opposition voters might experience after the election. Opposition parties have deprived their voters of a candidate, to whom they could relate, on whose behalf they would enthusiastically campaign, and for whom they would go to the polls. Had their candidate of choice possessed the political skills necessary to mobilize voters, their losses would be much more limited. Instead, we are faced with a long-term problem in Turkish politics with structural implications – all based on the ways in which opposition voters relate to the nation's politics.

The question is as follows: Why did the opposition make such a decision? Was it political miscalculation or a deliberate choice to pick İhsanoğlu and ensure a bitter defeat? In other words, why did the CHP and MHP endorse a candidate whose likely unsuccessful bid would create a political vacuum and drive their supporters toward feelings of defeat and victimhood? The first thing that comes to mind is that intra-party calculations were influential in this decision. Both leaders opted for a candidate who was not only obviously incapable of motivating voters but also could turn them away from the political process altogether in order to safely hold on to their positions. Unable to back their choice with a positive platform focused on the future, the opposition parties had little choice but to go with the politics of polarization – a safe option with guaranteed results.

Over the next weeks, the opposition will seek to persuade voters to go to the polls by fueling their dislike of Erdoğan, since the candidate and his platform have so far failed to perform this task. Surely enough, the degree of polarization and hatred toward Erdoğan will have a positive influence on the likelihood of voters going to the polls. In recent years, this strategy yielded such satisfactory results that the opposition parties simply embraced political laziness and even anti-politics. Main