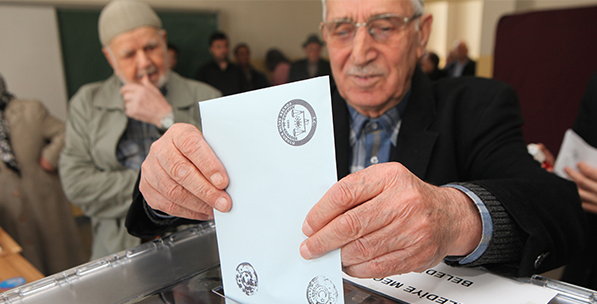

In modern democratic politics, one of the most effective instruments of attracting electoral support is extending pledges for better macroeconomic governance and improvement of social welfare. Following a long interlude during which pre-election discussions focused on ethno-religious identity politics and contrasting approaches to ideologies such as nationalism, Kemalism and secularism, Turkish politics seems to be heading in the right direction. As the countdown continues to the June 7 general elections, Turkey's main political parties have started to unveil their election manifestos and the majority of the pledges addressing the electorate relate to major reforms in the economic and social realms. Having led Turkey since 2002 with single-party governments, the incumbent Justice and Development Party (AK Party) is going to the polls with a clear advantage of having demonstrated its performance on macroeconomic and social policy implementation with concrete outcomes, but opposition parties have raised the stakes by promising extremely generous social support packages and substantial wage increases for the most disadvantaged groups in society. Hence, a very interesting and competitive election campaign awaits us.

Turkey's high and sustained economic growth performance between 2003 and 2012, despite the global crisis, has turned into a moderate growth path, largely owing to the decline in global demand and liquidity conditions. Therefore, it was expected that the economic competition among main political parties will concentrate on macro and micro-level proposals to revive the growth dynamism in the economy. Indeed the AK Party's election promises concentrate on reforms designed to revive small- and medium-sized enterprises, increase the inflow of foreign direct investment, accelerate research and development investments and technology transfers. Following a decade of policy emphasis on macroeconomic and financial stability, influx of foreign capital, the construction boom supported with easy credit and consumption driven service industries, it was accepted that Turkey needed a new development narrative through which the real economy, manufacturing sectors, knowledge-based industries and human capital strategies can be prioritized.

The main opposition Republican People's Party (CHP), long known as an ardent supporter of Turkish secularism and Kemalism, surprisingly prepared an economically-oriented election campaign. The CHP is specifically concentrating on those social sectors that were placed on the losing end of Turkey's rapid and market-led global integration under the AK Party - the unemployed, minimum wage earners, pensioners, industrial workers, traditional farmers and settlers around metropolitan ghettos. Yet the CHP's election manifesto promises ranging from cheap gasoline for farmers to doubling the minimum wage and pensions and from canceling credit card debt to cheap housing for the poor constitute a list of redistributive measures that are not placed in a prudent macroeconomic and budgetary framework. The CHP's image as a statist-bureaucratic political organization and its lack of innovative income-raising intelligence similar to that of AK Party led to critique of the financing of these pledges. Another opposition party, the Democratic Peoples' Party (HDP), which describes itself as the voice of the national Kurdish movement, also joined the economic contest by promising to triple the minimum wage, allowing free electricity and water for every family and increasing workers' social rights. The Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) is yet to announce its election manifesto, but it is also expected to give weight to socioeconomic pledges in line with its arch rivals.

The fact that ideology-dominated parties are moving toward an economic election platform is promising for the development of Turkish democracy, yet one needs to address the issue of economic prudence as well. Turkey has a structural current account deficit and if fiscal discipline is also lost to give way to substantial budget de