Last week Turkey witnessed a first. Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan broke his fast with 1,000 Alevis in Ankara. The fast was in observance of the beginning of the month of Muharram.

Turkish Alevis and other Shiite Muslims around the world observe these days as a period of mourning for the killing of Hussain, the grandson of the Prophet of Islam, and members of his family (Ahl al-Bayt) in the year A.D. 680 in a place called Karbala. This incident has played a significant role in the creation and crystallization of Shiite Islam. It has also been a source of friction between Sunnis and Shiites. Even though Sunnis have condemned the Karbala incident, Shiite Muslims and Alevis in Turkey have kept its memory more visibly and dramatically than the Sunni world.

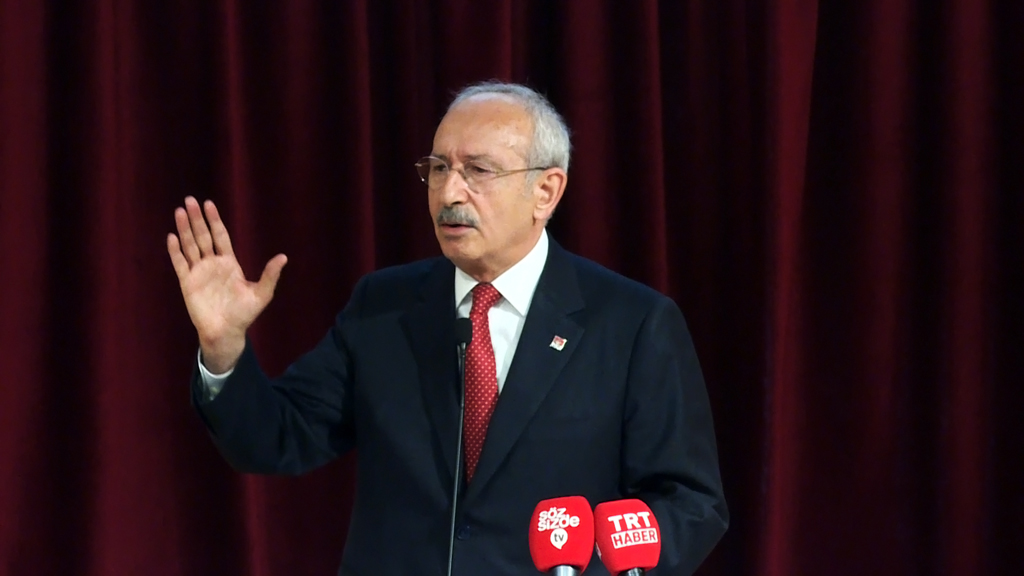

What was unique about the Muharram iftar with the Alevis? As we discussed on our TV program on TRT 1 last Friday, for the first time in the history of the republic, a Turkish prime minister sat with Alevis to share their mourning and participate in a typically "Alevi" event. Prime Minister Erdoğan gave a message of unity and solidarity and said that what unites Alevis and Sunnis in Turkey is more than what divides them. He also hinted that his government is ready to engage with the Alevis in a serious manner and respond to their demands.

This sounds familiar. Prime Minister Erdoğan made a similar call three years ago about the Kurdish issue. He was blasted for "recognizing the Kurdish issue" in a speech in Diyarbakır. Then came a series of visceral attacks on his credentials as prime minister, as a Turk, as a believer in the core values of the republic, in Kemalism, etc. Ever since then and until very recently, Prime Minister Erdoğan did not openly discuss the Kurdish issue. His government did not take any progressive steps to start a national process of reconciliation or a long-term solution. The issue was pushed to the margins of the Justice and Development Party's (AK Party) political discourse. Deputies from Kurdish areas did not dare speak out about the issue.

Everything changed with the July 22 elections. The AK Party shared Kurdish votes with the Democratic Society Party (DTP) in the region but got more support from Kurdish citizens nationally. The DTP's claims to be the only party to represent the Kurds in Turkey were shattered. The DTP's irresponsible politics of identity and its dismal failure to make any progress within the political system is now pushing the AK Party as the only party that can really take the bold steps for an enduring solution.

But the AK Party's dilemma is also its strength: As a center party, the AK Party has the credentials to deal with the Kurdish issue in a serious way. With the DTP almost out as a responsible political actor, the AK Party can propose a number of measures that will be acceptable to Kurdish citizens. But how will this reflect on its credentials as a center party? How will its central Anatolian and Black Sea constituency react to any bold move? How will the establishment react? Will it continue to watch the AK Party closely and suspiciously, or will it mobilize its well-known resources to trump up another political crisis?

These questions hold true for the AK Party's new Alevi initiative. As Reha Çamuroğlu, the AK Party's main Alevi deputy charged with coordinating the initiative, has said, the Muharram iftar was only the beginning of a long period of engagement. It will be followed by other moves and gestures, some symbolic, some concrete. Alevi institutions seem to be divided on the initiative. Çamuroğlu sees this as normal. There won't be any quick solution to a 1,000-year problem. Some Alevi groups who consider themselves to be outside the fold of Islam and want to grant the Alevis minority status are openly against the initiative. They seem to be a small minority but are surely a noisy one.

The same question again: Will the AK Party hold its ground vis-à-vis the new initiative when it is attacked by some extremist Alevis and perhaps question