During the 1990s, when the Welfare Party criticized the governing party using religious discourse it was considered a form of Islamism.

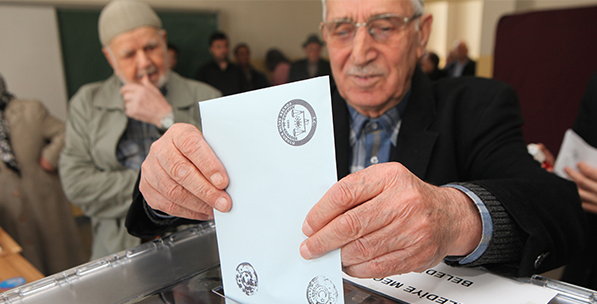

As we approach the March 30, 2014 elections, we bear witness to the manner in which all parties are using religious language at rallies.

Not all the existing parties in Turkey are Islamist of course. So then, how should we interpret the rise of religious discourse in politics?

This recent development, without a doubt, is a consequence of the Dec. 17 period.

During the 1990s, there was a lively discussion on democracy and secularism within the Turkish Islamic movement.

Despite the problems resulting from the Feb. 28 coup, the 2000s have been a decade during which some actors (the AK Party and the Gülen Movement) stood out as they defended the idea of integrating with the world and embracing democracy.

These actors, leaving Islamist language aside, were in a struggle to transform Turkey and move on to a post-Kemalist period.

Turkey's normalization period was shaken again on Dec. 17, 2014. This period has redefined the relationship between Islam and politics in Turkey and the instances in which religious discourse will be utilized in politics.

Such harsh religious discourse is not just a product of the struggle between the Gülen network and AK Party. All the political leaders at local election rallies are using slogans with religious overtones when speaking about wiretaps, the Gülen network and corruption claims.

Also, the political language of the Republican People's Party (CHP), which sees itself as the defender of secular politics, has become theo-political in nature. The mayoral candidates from CHP, who are criticizing the party in power with illegally obtained "evidence," are pushing this line even more in their campaigns.

In their brochures, they claim that "the true face of AK Party" is non-Islamic. Thus, the CHP's criticism of the AK Party is gradually overlapping with religious criticisms of the Gülen Movement.

The discussion of who is the "real Muslim" has never received such traction during any election in Turkey before.

The debate playing out over social media about cassettes and tapes has produced not a public debate but rather harsh religious accusations.

Thus, the use of religious discourse has been on the rise, deepening polarization within Turkish politics.

Different ideological and political positions feed on identity statements and are stiffening.

These statements vary from a religious group violating the privacy of the people through wiretaps to spying. The rise of harsh religious discourse is poisoning the language of the new Turkey which is supposed to be based on common values (such as deliberative democracy, rule of law, constitutional citizenship and secularism that respects Islamic demands).

What is more important is that if the struggling actors switch to embracing and democratic statements, it is possible they will have already lost credibility in the eyes of the public. For instance, a call from the Gülen network for a new democratic and comprehensive constitution will not be convincing unless they disassemble their parallel structure within the state.

Also, the inauguration speeches of the politicians have to champion more democratization. No matter how provocative, we have reached the limits of the power of discourse. If we go further, terms like "rule of law" or "democracy" will lose their meanings. The neutralization of discourses that are produced both based on democracy and rule of law, and of religious notions, may clear the way for the consolidation of Turkish democracy.

When there was nothing more to say on the Kurdish conflict, the reconciliation process began. We are entering a period where what really matters is not discourses and rhetoric, but rather practices. That is a place where everybody gets it off their chest, a place where weaponized harsh discourse will become ineffective. A point where s