Muslims represent the second largest religious community with approximately 1.4 million adherents in 2017 (3,1 percent of the whole Italian population). While Islam and Muslims were not a priority issue for Italian policy-makers for decades, the post-9/11 context led politicians to intervene more and more in Muslims’ daily life and worship. Between 2005 and 2017, Italian politicians made a set of rules aimed at regulating and controlling Muslims in Italy. Mostly motivated by security and counter-terrorism priorities, these policies tend to treat Muslims as internal enemies instead of viewing them as common citizens and potential partners in the public policy-making process. This situation has even further deteriorated these last months with the refugee crisis and the formation of the far-right/populist “Salvini-Di Maio” coalition government in the spring of 2018.

Initially, Article 8 of the Italian Constitution allows the representatives of each non-Catholic religious community to sign an agreement with the Italian state in order to regulate their mutual relations and support. Currently, it is only the Catholic Church that has benefited from a specific status since 1929. For other religious groups, any demand for agreements or accords with the state is followed by a long political and administrative process, and should be finally approved by both the government and the Parliament. Religious groups that are beneficiaries of such accords are the Catholic Church, the Confederation of Methodist and Waldensian Churches, the Seventh-day Adventists, the Assemblies of God, Jews, Baptists, Lutherans, Mormons, the Orthodox Church of the Constantinople Patriarchate, the Italian Apostolic Church, the Buddhist Union, the Soka Gakkai Buddhists, and Hindus. As for the Muslim communities, none of them are officially recognized by the Italian state.

Some argue that the Italian state aimed at filling this gap in 2005 by launching the “Consulta”, which is an advisory body composed of 16 members of the Muslim community selected by the government. Yet, this project, initiated by Interior Minister Giuseppe Pisanu (Forza Italia), did not lead to any consistent actions. In fact, this first trial, in a way, is an example of a public policy that attempts to shape Muslim communities from the top down, without involving Muslim citizens in the decision making process. Moreover, the Italian state’s security and counter-terrorism-oriented approach prevents it from adopting collaborative policies on Islam, namely, those that not only do not criminalize Italian Muslims but also aim at working with them hand-in-hand toward reaping mutual benefits.

A little more than a decade on, this biased approached was confirmed by two state-sponsored projects. In Jan. 2017, Interior Minister Angelino Alfano (from the New Centre-Right party, Nuovo Centrodestra) announced the creation of a new “Council of Relations with Italian Islam”, another advisory body whose official mission is to “improve the integration of Muslims in the country”. Its discourse and methodology are thus based on a security-oriented top-down approach. Angelino Alfano claimed that the Muslim members of the Council of Relations with Italian Islam would work towards the formation of what he called “an Italian Islam that would align the religion more with the country’s Christian and humanist tradition”. He also said the council aimed at further integrating Muslim immigrants, preventing extremism, training imams and validating the establishment of new mosques. The council is composed of so-called “academics and experts in Islamic culture” and it is to present proposals and recommendations on integration issues on a monthly basis.

One month after Alfano’s announcement, in Feb. 2017, the National Pact for an Italian Islam” (officially, “the National Pact for an Italian Islam, the expression of an open and integrated community, adhering to the values and principles of the Italian legal system”) was signed by Minister of Interior Marco Minniti (from the Democratic Party, Partito Democratico), the coordinator of the Council for Relations with Islam and nine Islamic organizations in Italy, among them the Union of Italian Muslim Communities (UCOII) -- the country’s largest Muslim organization; Muslim Brotherhood-linked --, the Organization of the Rome’s Grand Mosque (the biggest mosque in Europe), the Shiite “Ahl-Al-Bait” organization, the Muridiyya Sufi Brotherhood (of Senegalese origin), and the Albanian Muslim organization. The Italian government claims that these organizations represent more than 70 percent of Muslims in the country. Yet, this pact is not an agreement in the constitutional sense and does not provide advantages, such as public funds, the legal recognition of Islamic weddings, and giving Muslims days off for their religious holidays. Instead, the state is demanding that the Italian Islam’s representatives make a series of commitments, including giving their consent to the state’s training of imams, the management of the Islamic centers transparently, and the delivering of sermons in Italian. It should be noticed that such commitments have never been required of any other religious group in the country. The document also adds that the degree of respect shown to these commitments may pave the way for an official agreement between the state and Muslim communities.

The attempt to shape Muslims’ worship and lifestyle is a fact of decentralized institutions, especially universities and municipalities. In Oct. 2017, following this pact, the University of Bari (Apulia Region) launched a one-year M.A. course with the declared goal of “preventing radicalization and terrorism for supporting interreligious and intercultural integration policy”. The course also aims at training members of the police forces, the armed forces, the judicial power, as well as researchers, experts on national security, lawyers, journalists, university graduates from the fields of law, economics and humanities. The program deals with legal, political and strategic issues, with a specific focus on Islam. It also teaches surveying and risk prevention techniques, while investigating the sociological aspects and media profiles of the phenomenon that is terrorism.

Italian municipalities have also been making efforts to shape Muslims’ daily lives in different ways. In 2016, the regional council of Veneto and Liguria adopted laws that made the construction of mosques harder and the use of Italian compulsory, and it made the building of new Muslim places of worship contingent on the holding of local referenda. The same year, the municipality of Florence even signed a kind of agreement with the local Muslim community for imams to deliver the Friday sermon in Italian, to keep mosques open for the entire public, and to inform it on local religious and cultural events.

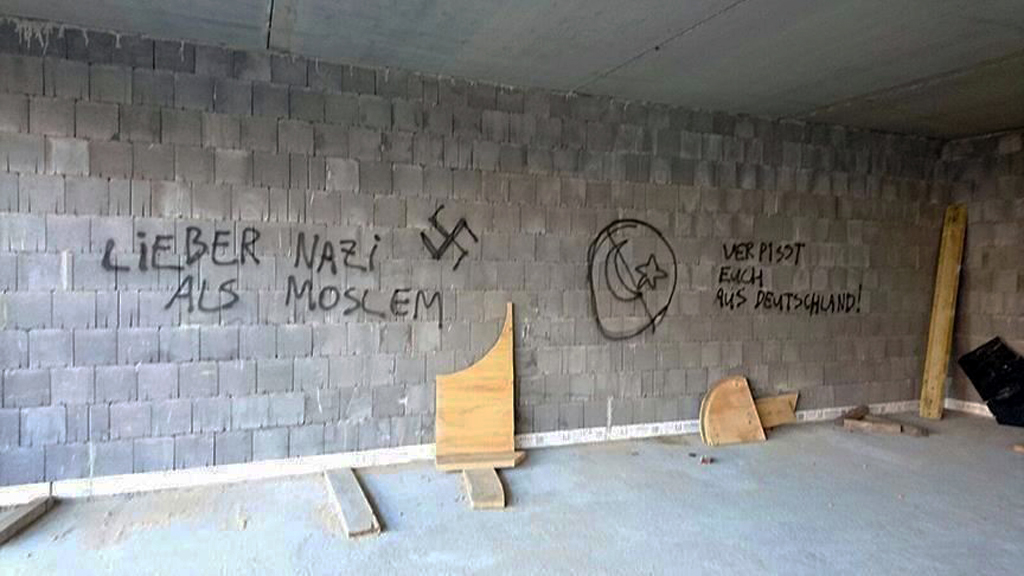

As a result, Italian policy-makers from the coalition government as well as local administrators tend to shape Muslims’ daily lives and rites of worship employing an approach that is solely based on what they call security concerns and counter terrorism efforts, while indefinitely postponing any official agreement between the state and Muslim communities. State initiatives do not take Italian Muslim citizens’ needs into account but instead try to impose priorities, discourse and methods on them. The interior minister, also the leader of the Northern League, Matteo Salvini, keeps repeating that “Italian culture and society are at risk of being eradicated by Islam” because of the “migrant invasion”. The other party in the coalition, the Five Stars Movement, does not only not contradict its new coalition partner’s Islamophobic rhetoric, but also supports its populist agenda.

[AA, 12 October 2018]