Almost two years ago, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe made a policy speech in Washington, D.C. called "Japan is back." Abe in his ambitiously named speech wanted to emphasize as much as possible that Japan will not become one of the declining powers and will be back in the game as a "first tier" country. In the introduction to this rather passionate speech, he said, "I am back and so shall Japan." Of course, in the two year period since this speech, Prime Minister Abe's economic program, also called Abenomics, gained significant attention in international political economy, and despite some debates about its fate (especially the potential outcomes of the third arrow of Abenomics, which entail important structural reforms in key industries in the country), many consider the program as the most courageous attempt to save and reboot the Japanese economy.

A month ago, Prime Minister Abe won a snap election, reaffirmed his position in the country and got approval for his aggressive economic policies. The election victory will provide him with a lot of leeway to continue the desired economic reforms and adopt, in some instances, not very popular measures. However, although Abe in a recent interview indicated that he wanted to be remembered for his attempts to reboot the economy, in the meantime he also faces some very significant social and diplomatic problems.

A major issue for Abe in his new term will be the continuation of his policy of an assertive and pro-active foreign policy in different parts of the world. Besides rescuing the economy, Abe also wants to demonstrate to the world that he has come back again and so shall Japan. In the last couple of days, it was seen that Japan's foreign policy team will continue to be very active in launching new initiatives, such as Japanese-Indian maritime security negotiations and providing new economic development assistance loans, which have been a significant part of Japanese diplomacy, especially in the third world. This will make the itinerary of Japanese foreign policy makers busier in the coming months.

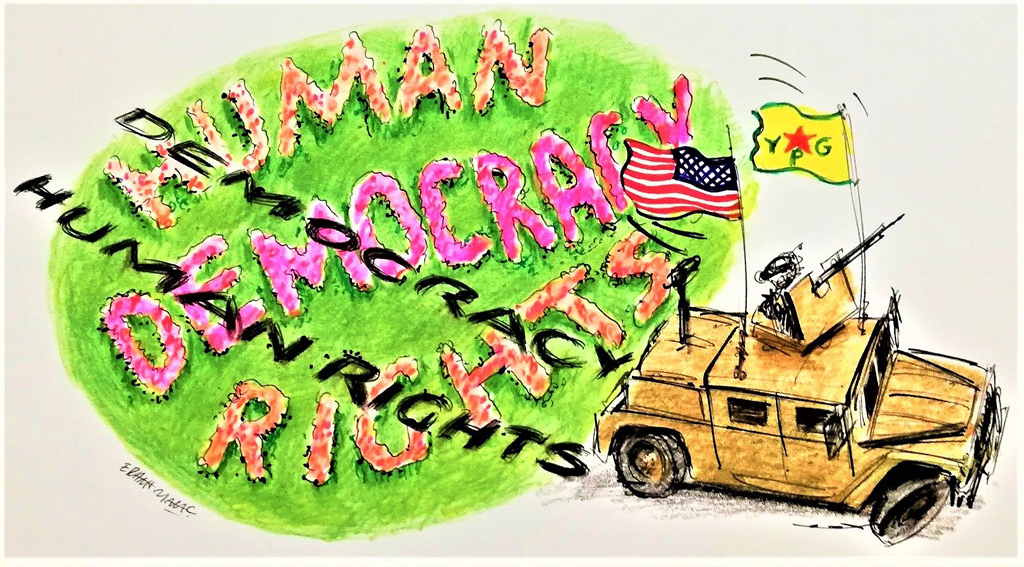

Without a doubt during these endeavors of Japanese foreign policy, the biggest help to foreign policy makers will be from the already existing soft-power and positive image of Japan in many parts of the world. Great confidence in Japanese goods, praise for the hardworking Japanese society and appreciation for Japanese development assistance have created a positive reputation for Japan in different parts of the world. This soft power has also been supplemented in recent years by the increasing circulation of Japanese popular culture products, including the mangas of Eiichiro Oda and Masashi Kishimoto, the novels of Haruki Murakami, animations of Hayao Miyazaki and the movies of Takeshi Kitano. However, despite this positive image and cultural influence, the operationalization of this soft power in terms of positive contribution to the resolution of international conflicts has been very limited. Prime Minister Abe in the same speech mentioned in multiple instances that Japan along with other democratic countries in the world wants to join efforts to protect human rights, promote rules and norms, fight against poverty, et cetera. This makes for a nice wish list for a democratic superpower that wants to make an impact in international relations. However, so far the Japanese government has not been involved in debates about human rights and democracy in the manner that Abe mentioned in his speech. Although financial assistance for countries around the world is a significant contribution of Japan, as a decades-old democracy in Asia, it can still make more meaningful contributions in the area of democratization in different parts of the world.

Without a doubt, security in the Asia-Pacific region and the crisis between Japan and its neighbors will be the most significant challenges that Abe will have to deal with. Despite some thaws in relations with neighbors, most of these thaws have been symbolic and in most instances cosmetic improvements. Senkaku